sources

- bad science

- diary of a teenage atheist

- new humanist blog

- pharyngula

- richard dawkins foundation

- sam harris

- skepchick

- richard wiseman

Powered by Perlanet

Connor Tomlinson is 27 years old, a regular commentator on GB News and a self-described “reactionary Catholic Zoomer”. But this wasn’t always the case. In a YouTube interview from 2024, Tomlinson says he was baptised as a baby but was “not a regular church attendee”. It was only, he says, in 2019 when conservative Christian friends inspired him to “make the grown-up decision to just believe it and see what happens” that he started attending weekly mass and was confirmed as a Catholic.

Soon afterwards, he began writing opinion pieces for Conservative media outlets before becoming a contributor to a group called Young Voices. Supported by the US-based Koch Foundation, the group helps to place young, right-wing commentators in prominent media roles. Since then, Tomlinson’s social media channels (he has more than 100,000 followers apiece on YouTube and X) have hosted hundreds of videos from a conservative Catholic perspective – ranging from rants about immigration to chats about everything that is supposedly wrong with women.

In one YouTube clip from 2023, Tomlinson and disgraced priest Calvin Robinson claimed that “seeking attention on social media [was] a form of digital infidelity … makes your man feel unwanted, and profanes the sanctity of your relationship”. Criticising both liberal and conservative women, whom Tomlinson referred to as “titty Tories”, they suggested that posting selfies online negated any worthwhile work these women may have done and advised them, quoting from the New Testament, to focus on “finding a good husband”.

Tomlinson and Robinson – and other Christian right-wing figures espousing misogynistic views – are gaining a disturbingly large following of young men, including in the UK. Over the last 20 years, the political divide between young British men and women has grown, with the former more likely to identify as right-wing and, according to a 2024 study from King’s College London, to feel negatively about the impact of feminism.

There has also been a growing narrative around disaffected young men turning to religion. Last year, the Bible Society reported a five-fold increase in the number of 18-24-year-old men attending church services in the UK since 2018. The report was based on self-reported data, and doesn’t reflect an actual rise in recorded attendee numbers, but it was nonetheless seized on as evidence that this demographic is turning to faith.

What does seem to be true is that parts of the “manosphere” – the umbrella term for men’s rights activists, pick-up artists, incels and others – are going Christian (or claiming to). It’s a shift that is being leveraged to gain legitimacy and influence for their misogynistic ideas in the outside world – including in political circles, such as via Tomlinson’s close friend and former Reform UK party candidate, 29-year-old Joseph Robertson.

Women and the downfall of humanity

Whereas the leaders of the manosphere often express a blatant hatred of women and a focus on manipulative pick-up techniques, figures like Tomlinson rely more on ideas of the perfect Christian family. But dig a little deeper and the lines between the two worlds begin to blur.

Take US author and so-called “Godfather of the Manosphere” Rollo Tomassi (real name George Miller). Tomassi, who gained fame with his “Rational Male” book series, teaches his followers that women with multiple sexual partners are “low-value”. He has also written that women use sexism as an excuse for their own unsuitability for professional careers.

For Tomlinson, women are unfit for doing 9-5 jobs, because they are “impressionable, led by material incentives and easily manipulated”. Therefore, he claims, it is the job of a man to “be the vanguard against the degeneracy that has wasted so many fertile years and the potential of women who are not ugly, who could’ve been someone’s wife”. Both he and Robertson are keen to blame all manner of societal problems on the contraceptive pill.

The only real difference is that, for Tomassi, these misogynistic beliefs legitimise men using and abusing women because that’s what “nature intended”. Meanwhile, for Tomlinson and other Christian figures, it compels men to take women under their wing and teach them how to live because that is “God’s plan”. In both worldviews, women are responsible for the downfall of humanity and only valued when serving the whims and needs of men.

But despite this overlap, both Tomlinson and Robertson are strongly critical of the manosphere. Tomlinson believes it “perpetuates the paradigm of the industrial and sexual revolutions ... which made men and women so maladaptive and unattracted to each other in the first place”. Robertson appears to agree with this and has written florid critiques of self-appointed manosphere leader Andrew Tate and the perils of pornography.

When we reached out to Tomlinson about his statements and their inherent misogyny, he told us that: “The time I spend with my wife, mother, grandmothers, friends, etc. matters more to me than if someone I don’t know calls me mean on the internet … Men should be considerate, compassionate, and chivalric toward the women they love and who love them. Women should return that compassion and consideration in kind. We may do it in different ways, but that’s the core of it. Ideology obscures those relationships, makes people think in zero-sum terms about competing categories, and is making people miserable … So you’re welcome to engage with what I’ve written and said throughout my career, and I hope you do so in good faith. But I don’t feel compelled to defend myself against such a bad faith charge as ‘You’re a misogynist.’ I would rather spend time with my wife.”

The "God pill"

Tomlinson may want us to think that his religious beliefs are in no way misogynistic. But the reframing of manosphere theories as the “Christian” way to think and live has been going on for several years, and is evident when we look at the trajectory of certain figures within the manosphere. Daryush Valizadeh (aka Roosh V) was one of the first. A key figure in the early manosphere, he taught a version of Tomassi’s beliefs as a pick-up artist – a man who uses coercion and manipulation to pick up women – via his lucrative Return of Kings website. In 2019, after disappearing from the scene, he returned with a blog post explaining that he had “received a message while on mushrooms” and was taking the movement in a new direction.

Having replaced the so-called Red Pill (a trope where “taking the Red Pill” reveals the unsettling truth of reality, in this case revealing women’s “true intentions”) with the “God Pill”, his commitment to misogyny remained the same, only now it was fueled by the teachings of the Russian Orthodox Church. While the rebrand lost him many fans, it opened the door for a new wave of manosphere influencers keen to present their misogyny as piety. No longer seeking to humiliate women by coercing them into sex, they were now “good guys” working to reinstil the supposed natural order of things.

Since then, other men have come into this space; like Tomlinson, Robertson, Calvin Robinson and other protege’s of far-right student organisation Turning Point UK. Justifying their hatred of women via pseudo-intellectual arguments and with reference to Christian teachings, they are far more appealing to men who wish to subjugate the other sex while avoiding associations with the bare-faced aggression and criminality of figures like Andrew Tate.

Even more alarmingly, convincing themselves and others that they are educated men working for God, these men have muscled their way into speaking engagements and onto national news channels like GB News and Talk. The groups they associate with include the anti-LGBT Christian advocacy group ADF Legal (which advised the Orthodox Conservatives, a pressure group with which Robertson is closely involved); the Family Education Trust, a group with evangelical ties whose policy suggestions have made it into parliamentary discussions (Robinson and Tomlinson attended their conference last year); and anti-abortion group Right to Life, for whom Tomlinson, Robertson and Robinson are all advocates. These groups seek to limit access to abortion, prevent children from learning about the LGBT community and push Christian and traditionalist beliefs into policymaking.

Framing their arguments as the only way to “save” the west, the people who truly benefit are white Christian men and the women who obey them. Feminists, people of colour, Muslims, the LGBT community and others have no role in their brave new world.

What's the appeal?

Many of these men also deny that they are “far right”, while holding beliefs in line with both ethnic and Christian nationalism. Ethno-nationalists believe that identity is based on ethnicity and culture, whilst Christian nationalists believe that Christianity is the only way to save race and nation. In both cases the words “race”, “culture” and “nation” relate only to the white, western world.

Examples of both are present in most of Tomlinson’s output. In an interview with the Daily Heretic, a YouTube channel hosted by journalist Andrew Gold who focuses on “culture war” topics from a right-wing perspective, Tomlinson said he was not an ethno-nationalist. But he also claimed that former Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was not “nationally English” and that only those who could trace their British ancestry back to the Neolithic era were truly British. He believes that Britain is a Christian country; a bold claim given that less than half of those asked on the most recent census identified as Christian and 37 per cent claimed no religion at all.

These attitudes appear to be spreading, and are voiced by some Reform UK party candidates, including Joseph Robertson. In a video posted to X last year, Robertson claimed that “the natal crisis gripping the west” was happening because “the sacred act of motherhood ... has been demeaned and discarded” by feminists, which has “disrupted the natural harmony between men and women” and was “derailing the proper course of western history”.

Part of the appeal of these figures comes down to delivery. Whilst the angry rants of Andrew Tate are easily dismissed, the calm manner in which Tomlinson et al present their ideas makes them more accessible. Whether they are telling their audience that they need to “bring back women shaming women” to enforce modesty, or that men should be “the rock upon which [their wife’s] emotional waves may break”, it is delivered with the calm confidence of a Man Who Knows What He Is Talking About.

And while many manosphere leaders are actively grifting their audience, Tomlinson and his cohort appear to believe their own hype. These are not angry old men who will wrap themselves in the flag while getting arrested alongside Tommy Robinson; they present themselves as young, relevant “intellectuals”. For an audience of lost young men, uncertain of their role in life, that is more than enough to trust them.

Crisis of belonging

In the course of writing my book Incel: The Weaponization of Misogyny, I have had extensive conversations with youth leaders and teachers. They have shown that there is a clear crisis of belonging among boys and men in their teens and early twenties. They have friends, but the friendships stop at the school gates – and a lack of community spaces sees them confined to their bedrooms and screens. The algorithms are designed to promote the most lucrative content, which is often the most controversial.

Faced with a polarised, rage-filled digital world, which punishes young men as either “Nazis” or “soy boys” (progressive men who are deemed less masculine because they care about women), it is possible to see the appeal of the Christian manosphere’s calm utopia, which seems to offer a middle ground.

But aside from increasing support for the far right and growing levels of misogyny, Tomlinson et al are offering young men a version of a life which is both socially and financially unfeasible. For the vast majority, it is no longer possible to survive on a single income. As with the tradwife movement, which sees influencers advocating for women to quit their jobs, marry and start a homestead, Christian manosphere figures are recommending that young men seek out a simple life with a simple wife, while they themselves walk the corridors of power funded by podcast subscriptions.

In the offline world, parts of the Christian establishment are taking steps to separate themselves from these divisive figures and boost their image as welcoming, egalitarian spaces. Last year, Calvin Robinson was dismissed from a US diocese of the Anglican Catholic Church after he appeared to mimic Elon Musk’s “Nazi-style salute” at their National Pro-Life Summit, and he has never been ordained in the Church of England despite completing his training at Oxford. A year earlier, the Free Church of England fired one of their reverends for posting multiple online videos in which he criticised “woke” topics and referred to progressive female ministers as “witches”. And the new Archbishop of Wales is an openly gay woman.

But for those in the Christian manosphere, this simply provides further proof of the British Christian establishment “going woke” and will see them drift deeper into extreme orthodoxy to justify their own positions.

Thankfully, there are many secular groups working with young men. Last year, Mike Nicholson, CEO of the group Progressive Masculinity, told me how his team were going into schools and creating spaces for young men to talk about issues in the online world. Explaining that they “don’t teach boys to be men” but “give boys the agency and the freedom to design the man that they want to be”, Nicholson said that when boys were challenged on harmful beliefs in a safe environment the response was “phenomenal”. He believes in the value of discussion. “This idea that boys and men don’t like to talk is an absolute fallacy,” he said. “In the right spaces, somewhere they feel safe, they love to.”

Parents concerned about their sons can also improve their communication. The PACE model, developed by an educational psychologist to help children through trauma, can be adapted to almost any family situation. An acronym that stands for Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy, it describes how to approach concerning child behaviour without showing fear or censure.

Young men are bombarded with digital hate on a daily basis. It is our job to provide them with a nurturing, safe environment in which they can be encouraged to think critically about online content and the way they interact with it. It’s vital to remember that young men consuming harmful content are seeking answers to internal questions, not validation for pre-existing beliefs. If we engage with them, we can lead them to healthier sources than the Christian nationalist movement.

This article is from New Humanist's Spring 2026 edition. Subscribe now.

It’s an old, old story: Nasty Unfaithful Sex-Crazed Man treats Poor Nice Monogamous Woman like crap. Everything explodes, and they all live divorcedly ever after. This is also the plot of singer Lily Allen’s latest album, West End Girl. Only here it has a fresh new twist: Nasty Unfaithful uses non-monogamy as a cover for his shitty behaviour, forcing Poor Nice Monogamous to (kind of) consent to him seeing other people.

Non-monogamy is becoming increasingly popular, with the growing acceptance that having only one romantic and sexual partner isn’t for everyone, and that there are other valid ways to conduct relationships. Advice about how to do it ethically isn’t hard to find: there are hundreds of books, websites, therapists and communities out there. The narrative arc of West End Girl is an absolute disaster movie, and an entirely predictable one. It’s a caricature of what to avoid: the bad communication, the fact that one partner clearly hates the whole idea and is being pressured into it, the attempt to implement rigid rules in order to “tame” the extramarital encounters. (The rules fail to do this, and are promptly broken anyway.)

But the story resonates deeply for so many listeners precisely because it is familiar. Anyone who’s spent time in non-monogamous circles (or, frankly, on any online dating platform) knows this story too, and these men. Every woman who ever fell for a modern Nasty Unfaithful can see herself in West End Girl, and now she has a whole album of (absolutely belting) new tunes with which to vent her feelings. So far so innocuous: new generations need new versions of old stories.

And this is a story. Allen describes West End Girl as “autofiction”. Crucially, this means it’s not autobiography: it’s a collaboratively made album, and some of the content is made up. The main character (Poor Nice Monogamous) is an alterego of Allen. She is the reluctant partner “trying to be open”, trying to be something she’s not. So many of us have been that woman, trying to defang our fears of abandonment with some kind of self-improvement project.

Did Allen the flesh-and-blood human really do the things the character does in these songs? Did her real husband, or the real “other woman”, do the things described? We’re invited to imagine that they did. The lines between real people and fictional characters are blurred in exceptionally clever ways.

Social media is part of the album, as well as part of the broader media landscape that feeds and is fed by it. Instagram, Tinder and Hinge all show up in the lyrics. The proximity of the album’s launch to the release of the last season of Stranger Things – starring Allen’s erstwhile husband – extended the tendrils of the Upside Down into the West End Girl storyline. The album’s promotional materials have caused a stir, particularly the specially branded butt-plug USB drives – a call back to the now infamous song “Pussy Palace”, where Allen’s alterego describes discovering her husband’s sex toy-laden New York City pad (which, again, may or may not be a real event).

Meanwhile, the storytelling itself gently invites the listener to blend life with performance: the first song on the album is about theatre and acting, and the inciting incident for the entire drama is that the narrator gets cast as the lead in a play, as Allen was in real life. The second song then describes a question posed by Nasty Unfaithful as a (fucking) “line”.

If all the world’s a stage, maybe all the world’s a concept album too. Where does West End Girl begin or end? And why does it matter?

As individuals, we relate the stories we consume to our own bodies, our own senses of self. The labels we use to refer to ourselves are tools of self-creation – be they dating app pseudonyms, metrics like height and age, or social roles (the Allen character describes herself variously as “mum to teenage girls”, “modern wife” and “non-monogamummy”). These are the ingredients for alchemising life and people into recognisable narratives.

In our late capitalist economy, those narratives are often structured by what or whom we possess, and what or who possesses us. As Allen sings: “You’re mine, mine, mine”. When you approach a relationship as a casting of another person in the role of your partner, you objectify them: they become supporting cast in the drama of your life.

Meanwhile, of course, they are busy doing exactly the same thing to you. Existentialists and romantic partners Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre disagreed on whether heteroromantic love could ever be more than a power struggle, each trying to “win” by objectifying the other. Beauvoir was the more optimistic of the two, but remained in a life-long open relationship with Sartre regardless. In Allen’s penultimate song, the narrator refuses to let her (ex-) husband “win”.

But this is about more than individuals. Media narratives play a key part in the social construction of romantic love itself, as well as in the construction of gender roles in romantic relationships. When we keep telling the same story over and over, we strengthen the grip of existing scripts.

West End Girl plays into the standard narrative: it’s men who want sex and therefore non-monogamy. Women who agree to it to try and make men happy will get screwed over and it will all end in tears. It’s obvious that misogynistically practised non-monogamy is no better or worse per se than misogynistically practised monogamy. But it’s more comfortable to demonise non-monogamy than to come to terms with the reality (and ubiquity) of misogyny. It’s easier to cling to the myth that monogamy would solve misogyny, if only men could keep it in their pants long enough. In the Paris Review, Jean Garnett calls West End Girl “a rather neat, crowd-pleasing, bias-confirming presentation of nonmonogamy that casts male extramarital libido as the bad guy and Allen as the victim.” Of course it is: that’s the story people want. That’s how you sell albums and concert tickets and branded butt-plugs.

Which brings us back to capitalism, and the sheer marketing genius surrounding West End Girl. The album is a giant invitation to chime in. It reads like a friend’s post on social media, on which we are expected to comment “you go girl!” and “yes, men are bastards who just want tons of pussy!” It’s chatty and unchallenging, rather like a patter song from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Trial by Jury, in which a late Victorian incarnation of Nasty Unfaithful gets hauled in front of a law court (and of course the theatre audience) to be judged for his abandonment of a Poor Nice Monogamous, offering in his defence the touching plea that “one cannot eat breakfast all day, nor is it the act of a sinner, / when breakfast is taken away, to turn his attention to dinner.” Edwin, though, is a caricature in a comic operetta. The trial-by-audience of Allen’s characters, and the real people behind them, is not a joke.

Sex sells. And people assume non-monogamy is just about getting lots of sex – an impression not exactly refuted by this album. In reality, non-monogamy takes many forms. Polyamory, for instance, is defined by openness to more than one loving relationship. But West End Girl is not a nuanced treatise on love. It is first and foremost a marketing triumph. Lily Allen and her collaborators are presumably making a lot of money out of all this. Is that, under capitalism, what passes for feminism?

This article is from New Humanist's Spring 2026 issue. Subscribe now.

The Washington Post ran an article with the provocative title, “These Patients Saw What Comes After Death. Should We Believe Them? Researchers have developed a model to explain the science of near-death experiences. Others have challenged it.” It’s obviously empty fluff, garbage of the kind that gets pumped out all the time to appeal to the gullible yokels in their readership. I’m not one of them. I also refuse to read the WaPo anymore (rot in hell, Jeff Bezos), but then, fortunately or unfortunately, the same article has appeared on Beliefnet, sans paywall. Now everyone can see how insipid the ‘evidence’ for life after death is. This article should present some evidence. It doesn’t. It’s the usual anecdotal silliness.

Here’s their big example.

After she dropped to her knees outside her home in Midlothian, Virginia, suffocating, after she was lifted into the ambulance and told herself, “I can’t die this way,” and after emergency workers at the hospital cut the clothes off her to assess her breathing, Miasha Gilliam-El, a 37-year-old nurse and mother of six, blacked out.

What happened next has happened to thousands who’ve returned from the precipice of death with stories of strange visions and journeys that challenge what we know of science. Last year, a team of researchers from Belgium, the United States and Denmark launched an ambitious effort to explain these experiences on a neurobiological level — work that is now being contested by a pair of researchers in Virginia.

At stake are questions almost as old as humanity, concerning the possibility of an afterlife and the nature of scientific evidence — questions likely to take center stage at a conference of brain experts in Porto, Portugal, in April.

“The next thing I knew, I was out of my body, above myself, looking at them work on me, doing chest compressions,” Gilliam-El said, recalling Feb. 27, 2012, the day she suffered a rare condition called peripartum cardiomyopathy. For reasons that aren’t fully understood, between the last month of pregnancy and five months after childbirth, a woman’s cardiac muscle weakens and enlarges, creating a risk of heart failure.

Gilliam-El, who had given birth just three days earlier, recalled watching a doctor try to snake a tube down her throat to open an airway. She remembered staring at the machine showing the electrical activity in her heart and seeing herself flatline. Her breathing stopped.

“And then it was kind of like I was transitioned to another place. I was kind of sucked back into a tunnel,” she said. “It is so peaceful in this tunnel. And I’m just walking and I’m holding someone’s hand. And all I’m hearing is the scripture, ‘Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death …’”

Please, please learn about the concept of confabulation. If you black out, when you resume consciousness, your brain quickly invents stories to fill the gap. They aren’t necessarily accurate. A trained nurse is going to be familiar with happens to patients who lose consciousness, and could overlay that on the period when she was actually non-functional. She’s also pre-loaded with religious mythology, and that gets stuffed into the constructed memory. It’s not evidence of anything.

I have a recent personal experience that applies. I too blacked out after a fall; I remember the pain of bouncing my skull off the sidewalk, and then the next thing was becoming aware that I was sitting in my office at work. I remember nothing of what happened between those moments.

But I quickly made assumptions. I must have (scenario A) got up, dusted myself off, and walked to work by force of habit. Or (scenario B) a pedestrian must have helped me up and sent me on my way, or (scenario C) a passing motorist pulled over and gave me a lift to the building, or (scenario D) an angel swooped down, clutched me to her soft downy bosom, and transported me to my office chair before giving me a revitalizing swig from the cask of whisky she carried in a cask on her collar. Do I have any evidence for A) my indomitable will, B) a pedestrian, C) a motorist, or D) an angel? No I do not. Some might be more likely than others, but I can’t claim I have any verifiable evidence for any of them.

Likewise, Gilliam-El knows she passed out in an ambulance — and we can find evidence for that — and that she regained consciousness in a hospital some time later — also based on evidence. But all the stuff about entering a tunnel and holding hands and hearing scripture, is an unverifiable invention of her brain.

That’s all these articles ever provide, a collection of stories people provide after periods of unconsciousness to rationalize their experience, and then calling them “evidence for life after death”. They’re not.

It’s always annoying that these ideas get “experts” who are unable to distinguish fantasy from evidence to support a popular myth.

Now could someone explain it to Elon Musk?

It must be sinking in already, since he has already backed down and refocused on the moon.

I was sent a link to an intensely irritating article. It was by an old man complaining that his kids don’t email or call him enough, so he decided to test them.

Eleven weeks ago, I made a decision that felt both petty and necessary. I stopped being the one who always called first. No more Sunday morning check-ins, no more “just thinking of you” texts, no more being the family communication hub. I simply stopped reaching out to my three adult children and waited to see how long it would take them to notice.

The silence that followed taught me more about modern family dynamics than any parenting book ever could.

Then he’s annoyed about how long it took them to respond, and wasn’t sufficiently appeased when they did respond, and argues that all the previous communications were shallow and insincere.

Grow up, Grandpa.

I have three grown kids who are living their own busy lives.

My oldest has a stable job in a law firm and recently got a raise, but more importantly has a new girlfriend and a solid circle of friends. He’s probably the most sociable of my kids.

My second son is a major in the army, stationed in Korea, with a wife and child. He’s extremely busy and in a position of responsibility.

My daughter is working in academia…already I sympathize and know what she’s going through. She also has a young daughter.

I don’t want any of them to feel guilt for living their own lives, and they don’t need to call me. I’m just proud that they’ve grown up to be good people I can respect. I’m content. I think their mother and me, to a lesser extent, have succeeded at life.

My life is less interesting than theirs, and I also don’t need to call them and talk about my latest adventures (oh yeah, I fell down and concussed myself, not exactly entertaining news). I’m fine to occasionally learning that they’re happy. If they need help they can count on us.

But please, our reward is to know that they’re living well. That’s enough that we can pat ourselves on the back and tell ourselves that we did well, and that is immensely satisfying. We don’t need constant reassurance.

Once upon a time, I was briefly exposed to the university fraternity system. My first year of college, I attended Depauw University in Indiana, which had a fairly conservative policy: your first year were required to live on campus, segregated dorms, and we could only apply to a fraternity or sorority in our second year or later, and I transferred to the University of Washington in my second year. When I arrived in Seattle, I got so many invitations to fraternity parties before classes started, I think because I had a 3.9 GPA and was a National Merit scholar — I had the potential to raise the average house GPA. I was popular, a novel experience! I attended one party, and that was enough.

The party started with beer on the front lawn. They were having a casino night inside, and they also had a giant slingshot on the roof for firing water balloons at people walking down the block…for fun, you know. Their house was adjacent to a sorority, and the two groups were taking turns flashing each other through the windows. As the party started, they started serving rather potent rum-and-cokes, and I was not in any sense a drinker, but I had to down a couple of them. I was totally blitzed early in the evening.

One thing I learned is that I cannot hold my liquor. Another thing I learned is that I am the most boring drunk on the planet. I spent the whole night at the craps table, throwing dice and staring owlishly at the results, estimating probabilities with a brain that no longer worked. Don’t invite me to your party if you expect an antic, table-dancing maniac, sorry.

I did not join any fraternity, was never invited to join one, and never attended another frat party. They were not my thing at all.

But I am not at all surprised at the news that a hazing event at Iowa’s Alpha Delta Phi was raided by the police, who found 56 shirtless young men standing in a basement, wet and covered with thrown food.

The willing victims were stupid sheep, reluctant to speak up about what was going on. The leaders of the fraternity were arrogant, truculent, and trying their best to avoid responsibility. The adults who were supposed to be in charge of managing the house were unavailable and the student leaders pretended to not know how to contact them. It was a beautiful example of what fraternities are actually for, for indoctrinating young people into a hierarchical culture of subservience, and it produces some of the snottiest chickenshit lackeys who will use the hierarchy to diffuse responsibility and allow stupidity to run wild. These are the future leaders of the United States.

I lived in sane, clean, dormitories for four years where we learned to get along in an egalitarian manner, and avoided the more stupid nonsense that the frat cultures demanded of you. They aren’t places for learning, or becoming a better person, or experiencing a good community — they’re for chiseling you into a corporate drone who will reflexively obey. They’re tools for churning out Republicans.

P.S. The fraternity was suspended for four years, and the national chapter is already complaining that that’s not fair.

With the great powers facing off and a global authoritarian slide, we are entering a new era of brazen propaganda. But for all those who keep their heads down, there are many more who refuse to go along with it.

In the Spring 2026 edition of New Humanist, we celebrate the heroes of free thought on the frontlines of the battle against dogma and ideology – from the Belarusian women standing up for democracy despite imprisonment and exile, to the poet translating Orwell into Chinese and the therapists helping people rebuild their belief systems after leaving religious groups.

We also hear from Harvard's Steven Pinker about defending America's besieged universities and historian David Olusoga about why we must revisit the story of the Empire.

Keep reading for a peek inside!

The Spring 2026 edition of New Humanist is on sale now! Subscribe or buy a copy online today, or find your nearest stockist.

Defend the truth!

We hear from six champions of free thought around the world about how to fight back against propaganda and protect the truth – including journalist Andrei Kolesnikov on Russia's last remaining dissidents, campaigner Zoe Gardner on how to fight anti-immigration misinformation, and climate and vaccine scientists Michael E. Mann and Peter Hotez on how everyone can do their bit to defend science.

"Today, harm is being done by the spread of despair and defeatism, some of it weaponised by bad actors like Russia to create division and disengagement. We are, in fact, far from defeat"

Breaking free from belief

A growing number of UK therapists are helping people "deconstruct" their beliefs after leaving high-control religious groups. Journalist Ellie Broughton meets the therapists leading the charge, and the clients working to rebuild their belief systems.

“Over time, losing your religion may start to feel less like a loss, and more like an opportunity to rebuild yourself from the ground up”

Inside the women’s prisons of Belarus

Women played a key role in the Belarusian pro-democracy movement that came to a head in the summer of 2020. More than five years later, hundreds of women are still being held as political prisoners or have been forced to live in exile. And yet, they refuse to give up. Journalist Alexandra Domenech hears their stories.

"Despite the government’s attempts to crush their spirits, the women who have emerged from penal colonies tell stories of defiance and solidarity"

Steven Pinker on America's besieged universities

Harvard's high-profile psychologist Steven Pinker has long argued that a lack of political diversity at US universities is skewing research – but now there's a new and more dangerous threat from the Trump administration. He spoke to us about why it's important to fight attacks on academic freedom, no matter where they come from.

"Professors and students have been harassed, fired, sanctioned and censored for constitutionally protected speech"

David Olusoga on Empire, religion in Britain – and The Traitors

Following the success of his BBC Two series Empire, historian David Olusoga explores the challenges of talking about the British Empire today, the influence of the Church in Britain – and why carefully-crafted logic got him nowhere on Celebrity Traitors.

"Much of the hostility towards anything to do with the Empire is just a desire to not have to hear difficult things about Britain"

Also in the Spring 2026 edition:

- Journalist Katherine Denkinson explores how the manosphere is using God to target young men

- Laurie Taylor digs into how life-changing rethinks can hinge on a single word

- Zion Lights looks at the biomedical breakthroughs giving us a reason to feel cheerful

- We can now study diseases to track people and fight crime, writes Oxford bioethicist Tess Johnson – but should we?

- Richard Pallardy explores the havoc that can follow when farm animals breed with wild species

- Award-winning comedian Shaparak Khorsandi on how Stranger Things united the generations

- BBC Radio 4 presenter Samira Ahmed on the new nouvelle vague

- National treasure Michael Rosen explores the history of the word "climate" in the latest edition of his language column

- Marcus Chown on how our tiny brains are able to make sense of the Universe

- Lily Allen's album West End Girl got everyone talking about non-monogamy – but it tells an old story, argue academics Carrie Jenkins and Carla Nappi

- Jessica Furseth on the undiluted joy of the Wes Anderson archives

- Jody Ray takes a tense but awe-inspiring tour of Libya

- We talk to Russian-British comedian Olga Koch about comedy, class and computers

Plus more fascinating features on the biggest topics shaping our world today, book reviews, original poetry, and our regular cryptic crossword and brainteaser.

Germans are masters of the biting parade float.

How do they make those things? We need to import some German artisans to teach us the skill.

David Olusoga is a British-Nigerian historian, author, presenter and BAFTA-winning filmmaker. He is professor of public history at the University of Manchester. His most recent television series “Empire” – which explored the history of the British Empire and its continuing impact today – aired on BBC Two last year.

Let’s start by talking about the BBC series Empire. What was the motivation behind it?

We have conversations about the British Empire in this country as if we are the only people involved, which, given the nature of empires, is not possible. We often ignore the fact that conversations about the Empire are taking place in those many countries that were formerly British colonies.

There was a huge debate about the meaning of the British Empire in India – historians like Shashi Tharoor are kind of superstar historians because their ideas and their writings about the Empire have become enormous. In the Caribbean, there’s incredible scholarship, but also heritage work and memorialisation.

This conversation about the Empire is not a monologue within this country. It needs to be a dialogue with the countries that were colonies or territories of the British Empire. So the aim is to try to explore the story of the Empire as a history that is being revisited by people across the world. Because more than two billion people are citizens of nations that were formerly British colonies or protectorates or dominions.

What has the reaction been like?

Most people’s reaction to most aspects of history is that it’s interesting – not that this is a challenge to who I am, or an insult to my nation. And the viewing figures for Empire – it was one of the most successful factual programmes on British television in 2025 – show that most people are willing to engage in recognising that there’s much about the Empire that we don’t know.

But we do live in a moment when there is a kind of rearguard action to defend an “island story” version of the Empire, which takes any acknowledgement that the British Empire, like all empires, was at times extractive [as an unfair criticism].

What’s your response to this defensive attitude?

The British Empire lasts 400 years. It involves millions and millions of people, and there are all sorts of motivations and actions and behaviours that range from the genocidal to the purely altruistic. But the structure of an empire ... people don’t set sail to set up colonies in order to benefit the people who already own the land. Empires, by their nature, are about the mother country, the imperial power, more than the colonies.

But the expectation is that this is a history that must be dealt with as a piece of historical accountancy – that if you cover [a negative aspect of the Empire, you must cover a positive one]; if you talk about the Indian famines, you must talk about the Indian railways. When I write about the First World War, nobody ever confronts me for talking about the strategic failures of the generals on the Western Front, or the death toll, or the suffering in the trenches. This only happens with the subject of the British Empire, and particularly anything to do with slavery, where we suddenly feel that we have to be talking in terms of “balance”.

Much of the hostility towards anything to do with the Empire is just a desire to not have to hear difficult things about Britain, and they’re only difficult if you have a magical and exceptional view of Britain, that Britain is a nation unlike every other nation that’s ever existed in all of human history.

Does your work on the Empire feel personal? The phrase that people sometimes use is “we are here, because you were there,” right?

I don’t really think about myself that much, because I don’t look to history to give me a warrant to exist in my own country. There is this idea on the far right that the history of Empire and black history are ways of people of colour claiming their right to be in Britain. I don’t feel that needy. I pay my taxes, I contribute to my society. I don’t need there to have been earlier generations of black people in Britain.

However, I do deploy my background within story-telling, because I’ve been making television programmes as a producer and presenter for a long time, and I’m very good at understanding how to use your own experiences to make stories more impactful. So we end the Empire series with me deploying my ancestors to make the point that confronting the history of Empire, recognising it as part of our history, is not something about guilt or pride.

My Nigerian ancestors were in a town called Ijebu Ode in the 1890s that was attacked by the British, so I’m descended from people who were attacked by the British army. But one of my ancestors on my mother’s side was a Scottish soldier in the pay of the East India Company. So, if I did history in the hope of eliciting guilt from white people, I have a rather large Achilles heel.

I’ve experienced something similar myself. I read a review of one of my books about scientific racism, which argued “well, he would think this, because he’s half-caste.” That’s not a word I would use myself. But I still had a moment of self-reflection, asking myself, “would I be making the same arguments if I didn’t have Indian parentage?” I concluded that the answer was yes, but it stung me in a peculiar way.

These arguments aren’t arguments. They’re attempts at silencing people, at saying that certain voices saying certain things are illegitimate. What these arguments are all saying is, “I don’t like what this history is saying. Therefore, it’s not real history.” It is easier to attack the messenger than it is to deal with something that you’re uncomfortable with.

Episode two of Empire was particularly striking for me, because it’s about a story that I think isn’t well told – about this period of indenture. As you know, my great-grandparents were Indian indentured slaves (I’ve made a personal decision to use the word “slaves”) brought to Guyana. Could you describe what happened in this period?

In some ways, after slavery was outlawed, the British went back to what they had before slavery, which was the indenture system. British poor people would sell their labour for a period of years – five, sometimes 10 or longer – and they were transported to the colonies. They would then work for a free settler for those number of years, and at the end of it, they were freed. (If they were lucky; this didn’t always happen.)

But the story of indenture from one part of the Empire to another is particularly unknown because there’s no connection to Britain. In the case of India, somewhere between one or two million Indians left to become indentured labourers. There was a huge range of experiences – from the murderously exploitative to, you know, extremely positive for people being able to transform their lives, escape caste, buy land. It’s a system that lasted from the early 19th century, with some stops and starts, right through until almost the First World War.

Can you tell us about how your family got here?

My father was from Nigeria. He was studying here in Newcastle [when my parents met]. Then my parents moved to Nigeria and I was born there. They then separated and we moved back to the UK. So I’m a 1970s story of movement around former Empire connections, because Nigeria had been a British colony. I grew up in Gateshead, near Newcastle, and it was not a very diverse place in the 70s and 80s. It still isn’t. I was brought up in a white, working-class world with my grandparents and my mum and siblings. I have a strong feeling of affection for the north-east and a strong sense of belonging and identity to that.

What’s your family’s relationship with religion?

My mother worked really, really hard to not ever say what she felt, and we went through a normal comprehensive school system with the sort of religiosity and religious education lessons that you’d expect. It [the existence of God] just always struck me as really unlikely.

But I remember being young and thinking that believing in this stuff was part of being good, and I wanted to be good and to do my homework and not get in trouble and not upset my mum. So there was a feeling of “you should believe in this, and you should say the prayers and sing the carols” and all that sort of nonsense. There was a brief period when I went to Sunday school, because it was what you did if you were trying to be a good boy. But that clashed with the fact that I just always felt it was nonsense.

As I got older, I just wanted nothing to do with it. One of the challenges I’ve had as a historian is that I’m so disinterested in religion. And I’ve had to make myself [engage with it] because you can’t study the past when for almost everybody, part of their calculations, for every action that they took, was what was going to happen to their mortal soul. So I forced myself to read religious history, and particularly around the early Church, which was the university of the world. It was the centre of learning.

What about the relationship between the Church and chattel slavery?

The Church was involved in justifying slavery, but it was also involved both with the abolitionists and with enslaved people themselves, who found inspiration in the biblical stories – the obvious stories of Pharaoh and the escape from Egypt. So it was involved in every aspect. There were religious figures who justified slavery. There were religious organisations and individuals who owned enslaved people, who promoted and propagandised for slavery. And there were religious voices who were motivated by their religiosity to oppose it.

And the influence of the Church today?

I do resent living in a country where it is very difficult to educate your children without them being indoctrinated in religion. I believe in absolute toleration, but I am opposed to religious privilege. I don’t see why we have bishops in the House of Lords, having power in our political system. I don’t accept that collective acts of Christian worship should be imposed upon my child, or anybody else’s child. I also think that religious schools are becoming increasingly a force for disunity in the country.

It felt significant that Tommy Robinson did a Christmas carol service last year, which attracted more than a thousand people, and he’s had support from figures like Elon Musk. What do you think about Christian nationalism in the US, and the efforts to export it over here?

I think it’s people with a lot of money who can’t accept how different Britain is to America. You can’t have Christian nationalism in a country that’s essentially not a Christian country. But if you’re trying to keep your American paymasters happy, if that’s where the money coming in from America to foment greater division in Britain is coming from, then you have to do what your paymaster says.

Last time I went to church, it was young Nigerians and very old white British people. And if you go to a Catholic church in many parts of this country, everyone’s Polish. So if you’re interested in bums on seats, Tommy Robinson is not the obvious conduit to achieve that.

I’d like to see him go to church in north-east London with a big Nigerian community. See how he gets on there. But before we end this interview, we have to talk about something more light-hearted. Your appearance on the The Celebrity Traitors.

I was somehow in the final, which has been one of the most watched moments in recent TV history. It’s been interesting being involved in something, at this very difficult time, that made people really happy. Sadly, what made them really happy was seeing those of us who appeared to be incredibly incompetent. So it would have been nice to have made people happy with competency, rather than incompetency.

Rather than incompetency, wasn’t it that you were making very rational, evidence-based arguments, that were just always unfortunately wrong?

I’ve been trying to think about what happened. I spend my life reading, gathering evidence, and then trying to weigh it out, but when there was no evidence, I entered this kind of desperate starvation state, looking for it. I think my theories were entirely rational, but they were also entirely wrong. So for example when Stephen Fry suggested that we should not have discussions at the roundtable and instead we should just vote, most people went, “That’s interesting, Stephen,” and I went, “That would be really useful if you were a traitor.”

So you went for him.

You know, in lots of Victorian novels, there’s the boring accountant that the young woman doesn’t want to marry, and then the exciting cavalry officer? I feel I proved myself to be the boring accountant.

You’re Daniel Day-Lewis in A Room With a View.

Exactly. I should have been the young guy with my chest out, in the field, kissing Helena Bonham Carter.

Did doing The Traitors help restore your faith in TV? This is an industry that is slowly being eroded, and the BBC is constantly under attack.

Well, it didn’t change the BBC being under attack – we’ve lost a director general since Traitors went out. But it is a phenomenon. When I was a kid, when everyone watched something, the whole nation had been through this shared experience. It’s very rare now. The big TV hits of last year were Adolescence and Traitors; they couldn’t be more different but they both began national conversations.

But my passion for TV is because that was a way I could do history. I had a kind of fork in the road. I had to choose the academic path and the PhD that was in front of me, or do something else, and I wanted to do history in the way that it had enraptured me when I was young, which was watching it on television. The person who made me want to do TV – alongside my history teacher Mr Faulkner – was [the historian and BBC presenter] Michael Wood.

But also, I was brought up in a council estate. I had that deep fear of debt that people brought up with no money have. TV offered me a way of doing history and getting paid. Meanwhile, a sector like academia, in which you have to self-fund the necessary qualifications to advance, is closed to a great majority of the population.

What is it about Michael Wood’s work that particularly inspired you?

He did In Search of the Dark Ages and a whole series of different history projects with the BBC. He was often talking about what we don’t know. And I love the idea of unknowability. That’s what I try to do on television, to get to that precipice of what is knowable and unknowable, and then ask questions of the view.

The magic of history is that you can know enough to empathise with people who lived and died before you were born. You can imagine yourself in their situation, and that connection with people of past centuries is a magical thing. I feel deeply emotional about history. Sometimes I’m in an archive, thinking about someone who’s been dead for 100 years. I’m the only person in the world thinking about their existence.

Talking about humanism, it’s that idea that they [people from history] are exactly the same as me, and that I can imagine what they must have gone through, what the city that they walked through was like, and how different it is from the one of today.

I think exactly the same about evolutionary history. It’s just that the history I study is a bit older than yours. For example, the peopling of the Americas is a big question. And a couple of years ago in White Sands, New Mexico, they discovered fossilised footprints that put the date of people there several thousand years earlier than we’d previously thought. The paper described the prints of a young person, possibly a teenager, going out for a looped walk, which lasts about a mile. And at several points there are the footprints of a two or three-year old, but they come and go. So that’s a person with a toddler, and the toddler’s tired, and you pick it up, and it walks for a bit. Twenty thousand years ago, people were doing exactly what you do in a park on a Sunday morning with your child. That is what you’re talking about, for me.

I remember that. Maybe it’s because I was new to fatherhood when it came out. But just ... the universality!

So, what’s next? Will you be doing Strictly Come Dancing?

It’s been mooted. I think I could do Strictly for one reason, which is that I’ve spent a lot of my life fighting against racial stereotypes. And I could destroy the racial stereotype that all black people can dance. But no, I think the country has suffered enough.

This article is a preview from New Humanist's Spring 2026 issue. Subscribe now.

I recently ran a session at the University of Hertfordshire on the 7 factors that I believe underpin an impactful presentation.

While preparing, I was reminded of a conversation I had with a hugely knowledgeable director who had worked with many magicians. He explained that magicians often weaken their performances by letting the audience experience the magic at different times.

Imagine that a magician drops an apple into a box and then tips it forward to show that the apple has vanished. The box must be turned from side to side so that everyone in the audience can see inside. As a result, each person experiences the disappearance at a slightly different moment and the impact is diluted.

Now imagine a different approach. The apple goes into the box. The lid is pulled off and all four sides drop down simultaneously. This time, everyone sees the disappearance at the same time and the reaction is far stronger.

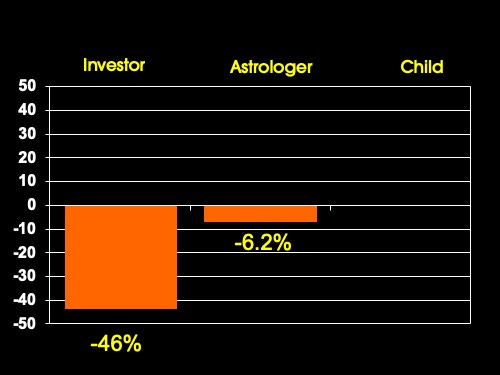

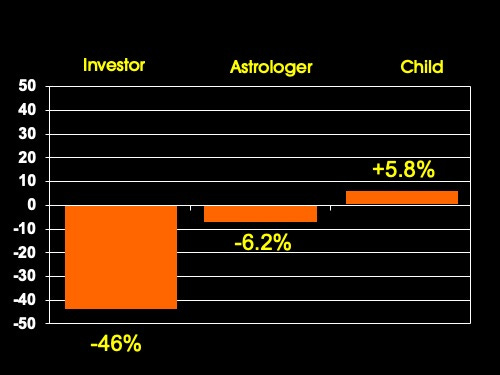

The same principle applies to talks. Some years ago, I ran a year-long experiment with the British Science Association about investing on the FTSE 100. We gave a notional £5,000 to a regular investor, a financial astrologer (who invested based on company birth dates) and a four-year-old child who selected shares at random!

If I simply show the final graph, people in the audience interpret it at different speeds. Some spot the outcome instantly. Others take longer. The moment fragments.

Instead, I build it step by step. First, I show a blank graph and explain the two axes.

Then I reveal that both the professional investor and the financial astrologer lost money.

Finally, I reveal that the four-year-old random share picker outperformed them both!

Now the entire audience sees the result at the same moment — and reacts together. That shared moment creates energy.

It’s a simple idea:

Don’t just reveal information. Orchestrate the moment of discovery.

If you want bigger reactions, stronger engagement, and more memorable talks, make sure your audience experiences the key moments together.

My new year began not with resolutions, but with tentacled monsters menacing 1980s children and their trusted adults. At the crack of dawn, I was on the sofa with my 12-year-old daughter, gripped by the Stranger Things series finale.

Watching TV with my children is one of life’s great joys – and at 12, my daughter is at the in-between age when the pool of shows we both love watching isn’t all that vast yet. Stranger Things bridges the gap between us so perfectly that for a couple hours she forgot I was her desperately uncool mother. I was a fellow adventurer flying with her through the Upside Down, entirely absorbed in the fate of the characters we have watched grow up and grown to love.

This used to be the simplest pleasure: watching TV with your family. One set, one channel and everyone in the same room. The chances of a shared experience diminished once we could watch our favourite shows on a train or during a challenging bowel movement. And this speaks to the great paradox of being a Generation X parent. We are forever explaining to our children that we were exactly like them once, while also insisting that our childhoods were completely different.

We had no internet, no phones, no streaming platforms – yet we were the modern generation. We had E.T. and Star Wars. We skateboarded without helmets and drank drinks that glowed in the dark. We were supposed to remain eternally youthful, preserved in the amber of grunge and VHS. So the creeping suspicion that our children might see us as old is frankly unbearable.

This is why Stranger Things has been such a joy and relief. Set in the 1980s, it should by rights be pure nostalgia syrup: bikes, basements, synths, curly hair that crunches. Yet somehow it surpasses that. The kids in the midwestern town of Hawkins don’t feel like retro relics. They feel startlingly like Gen Z: clever, funny, emotionally alert, but with more face-to-face bullying than online.

Then there’s the particular joy of Winona Ryder in the series. In the 90s, she was my complicated dream girl, the patron saint of dramatic eyeliner. I so wanted to be like her. Now she’s playing a frazzled single mum – just like me (sort of). Watching her character develop, as her anxiety strengthens into iron-willed protectiveness, has been unexpectedly moving. The show is a meeting point of generations, where Winona is still cooler than all of us combined.

That said, sometimes there are little jolts. Like when Will came out as gay, and my daughter informed me that “there was way more homophobia in the 80s, so Will is really brave and really felt he was risking losing his friends”. She said this, very earnestly, as though I wasn’t from that decade myself, when Section 28 set hatred into law. She speaks as though the 80s weren’t a real period of time, but more like a historical reenactment village.

But there’s something beautiful about that too. My daughter feels ownership over the 80s of Stranger Things – not as my past, but as her story-world. She meets me there, half in history, half in fiction. And for a moment, the generational performance drops away. I’m just a person who was once a child, watching children navigate the strangeness of growing up, next to my own actual child doing the same.

The finale of the show left me aching for my own childhood, where there were endless, wide-open skies of possibility. The writers, Matt and Ross Duffer, in their creation of a world that is part Star Wars, part Godzilla and part Eastenders, gave a glorious piece of my childhood back to me for a moment. As Bowie’s “Heroes” rang out in the final credits, I sobbed and said to my daughter, “See darling? The wonder, the magic never leaves us! It just changes shape and we forget to look for it, but it’s there, darling, the wonder is always there.”

She raised her eyebrows and got up, muttering, “Oh my god, Mummy, it’s just a show”.

This article is a preview from New Humanist's Spring 2026 issue. Subscribe now.

This week we have a quick quiz to test your understanding of sleep and dreaming. Please decide whether each of the following 7 statements are TRUE or FALSE. Here we go….

1) When I am asleep, my brain switches off.

2) I can learn to function well on less sleep.

3) Napping is a sign of laziness.

4) Dreams consist of meaningless thoughts and images.

5) A small amount of alcohol before bedtime improves sleep quality.

6) I can catch up on my lost sleep at the weekend.

7) Eating cheese just before you go to bed gives you nightmares

OK, here are the answers…..

1) When I am asleep, my brain switches off: Nope. When you fall asleep, your sense of self-awareness shuts down, but your brain remains highly active and carries out tasks that are essential for your wellbeing.

2) I can learn to function well on less sleep: Nope. Sleep is a biological need. You can force yourself to sleep less, but you will not be fully rested, and your thoughts, feelings and behaviour will be impaired.

3) Napping is a sign of laziness: Nope. Your circadian rhythm make you sleepy towards the middle of the afternoon, and so napping is natural and makes you more alert, creative, and productive.

4) Dreams consist of meaningless thoughts and images: Nope. During dreaming your brain is often working through your concerns, and so dreams can provide an insight into your worries and help come up with innovative solutions.

5) A small amount of alcohol before bedtime improves sleep quality: Nope. A nightcap can help you to fall asleep, but also causes you to spend less time in restorative deep sleep and having fewer dreams.

6) I can catch up on my lost sleep at the weekend: Nope. When you fail to get enough sleep you develop a sleep debt. Spending more time in bed for a day will help but won’t fully restore you for the coming week.

7) Eating cheese just before you go to bed gives you nightmares: Nope. The British Cheese Board asked 200 volunteers to spend a week eating some cheese before going to sleep and to report their dreams in the morning. None of them had nightmares.

So there we go. They are all myths! How did you score?

A few years ago I wrote Night School – one of the first modern-day books to examined the science behind sleep and dreaming. In a forthcoming blog post I will review some tips and tricks for making the most of the night. Meanwhile, what are your top hints and tips for improving your sleep and learning from your dreams?

I am a huge fan of Dale Carnegie and mention him in pretty much every interview I give. Carnegie was American, born in 1888, raised on a farm, and wrote one of the greatest self-help books of all time, How to Win Friends and Influence People. The book has now sold over 30 million copies worldwide.

I first came across his work when I was about 10 years old and read this book on showmanship and presentation….

According to Edward Maurice, it’s helpful if magicians are likeable (who knew!), so he recommended that they read Carnegie’s book. I still have my original copy, and it’s covered in my notes and highlights.

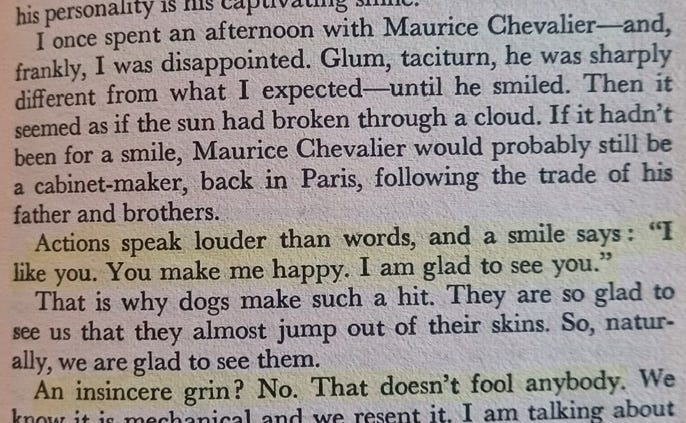

One of my favourite — and wonderfully simple — pieces of advice is to smile more. Since the book was written, psychologists have discovered lots about the power of smiling. There is evidence that forcing your face into a smile makes you feel better (known as the facial feedback hypothesis). In addition, it often elicits a smile in return and, in doing so, makes others feel good too. As a result, people enjoy being around you. But, as Carnegie says, it must be a genuine smile, as fake grins look odd and are ineffective. Try it the next time you meet someone, answer the telephone, or open your front door. It makes a real difference.

In another section of the book, Carnegie tells an anecdote about a parent whose son went to university but never replied to their letters. To illustrate the importance of seeing a situation from another person’s point of view, Carnegie advised the parent to write a letter saying that they had enclosed a cheque — but to leave out the cheque. The son replied instantly.

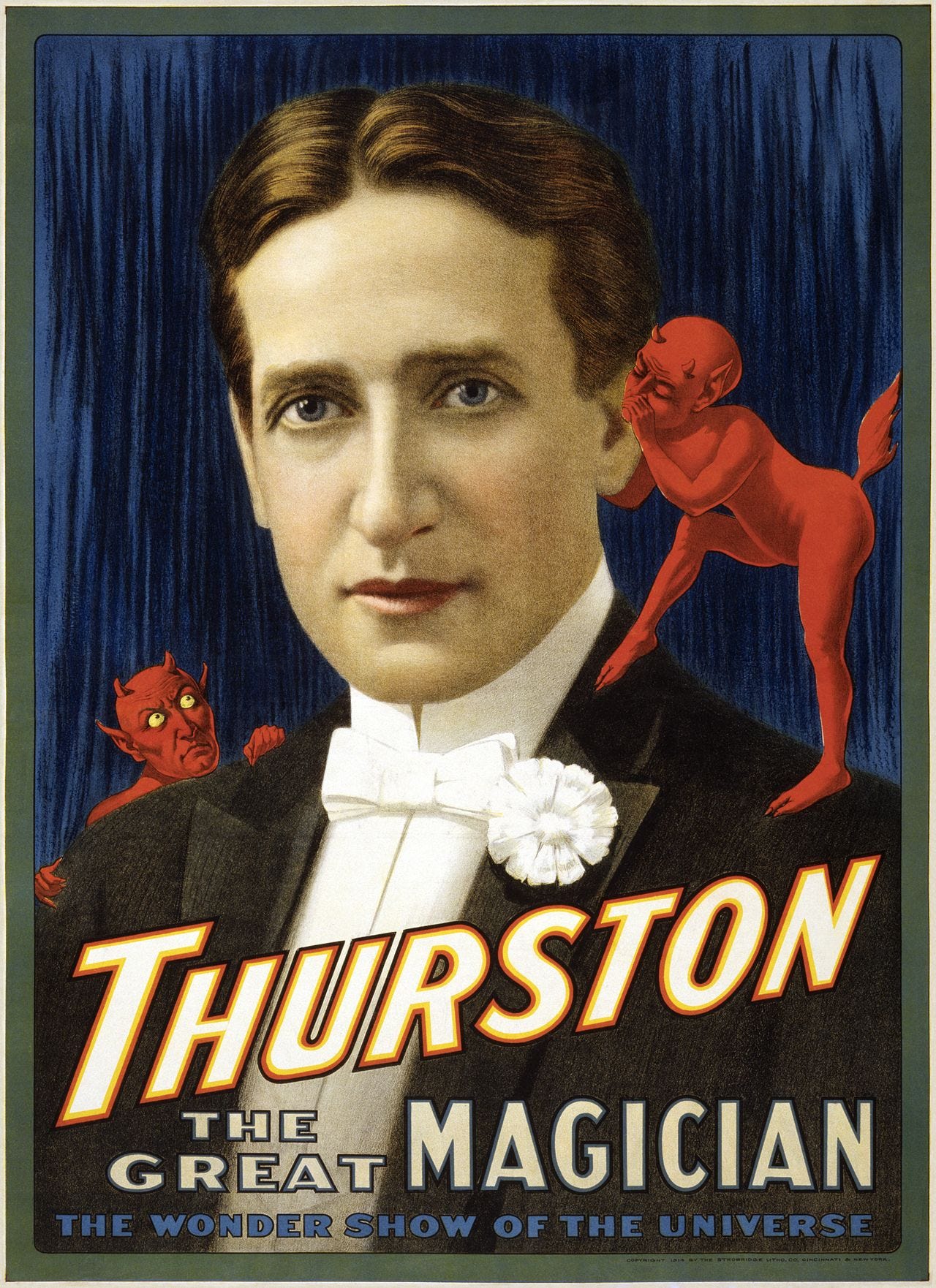

Then there is the power of reminding yourself how much the people in your life mean to you. Carnegie once asked the great stage illusionist Howard Thurston about the secret of his success. Thurston explained that before he walked on stage, he always reminded himself that the audience had been kind enough to come and see him. Standing in the wings, he would repeat the phrase, “I love my audience. I love my audience.” He then walked out into the spotlight with a smile on his face and a spring in his step.

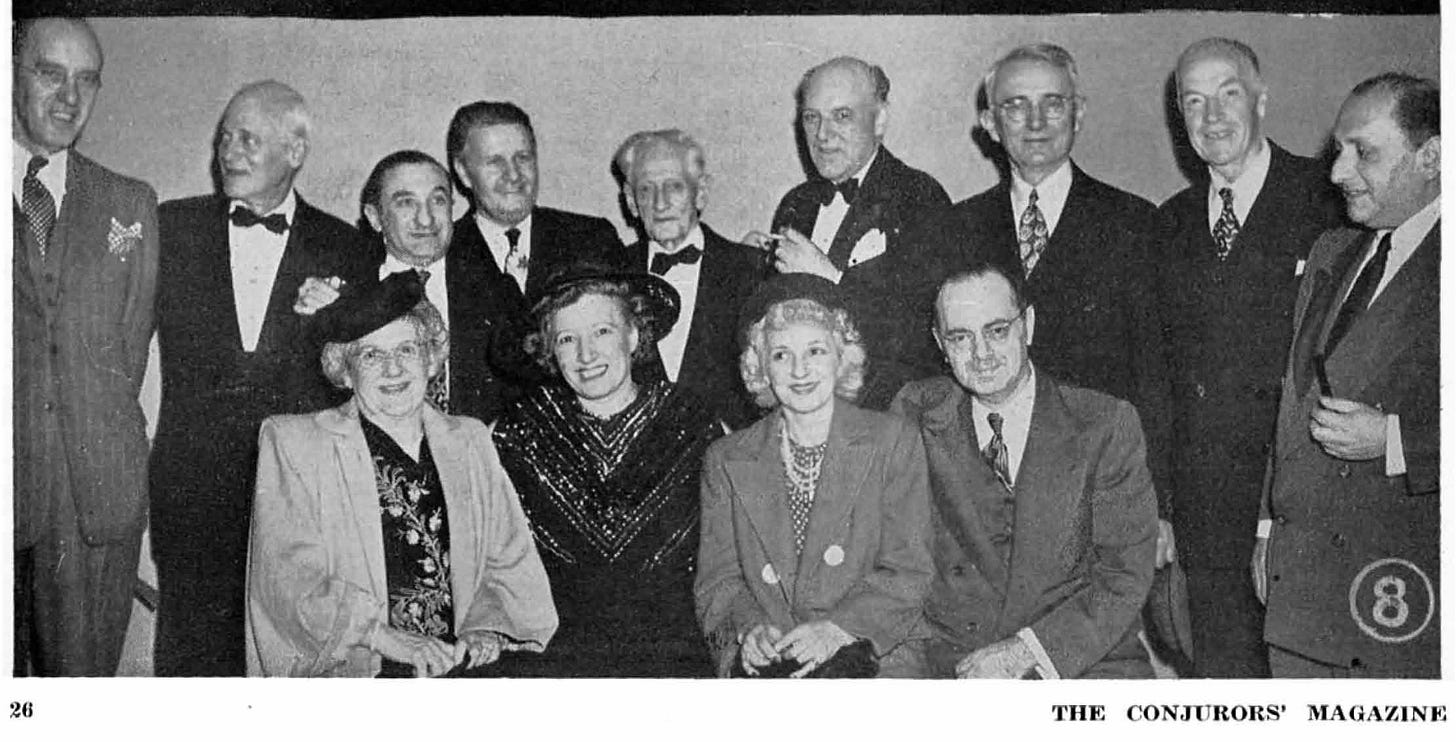

This is not the only link between Carnegie and magic. Dai Vernon was a hugely influential exponent of close-up magic and, in his early days, billed himself as Dale Vernon because of the success of Dale Carnegie (The Vernon Touch, Genii, April 1973). In addition, in 1947 Carnegie was a VIP guest at the Magicians’ Guild Banquet Show in New York. Here is a rare photo of the great author standing with several famous magicians of the day (from Conjurers Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 4; courtesy of the brilliant Lybrary.com).

Front row (left to right): Elsie Hardeen, Dell O’Dell, Gladys Hardeen, J. J. Proskauer

Back row: E. W. Dart, Terry Lynn, Al Flosso, Mickey MacDougall, Al Baker, Warren Simms, Dale Carnegie, Max Holden, Jacob Daley

If you don’t have a copy, go and get How to Win Friends and Influence People. Some of the language is dated now, but the thinking is still excellent. Oh, and there is an excellent biography of Carnegie by Steven Watts here.

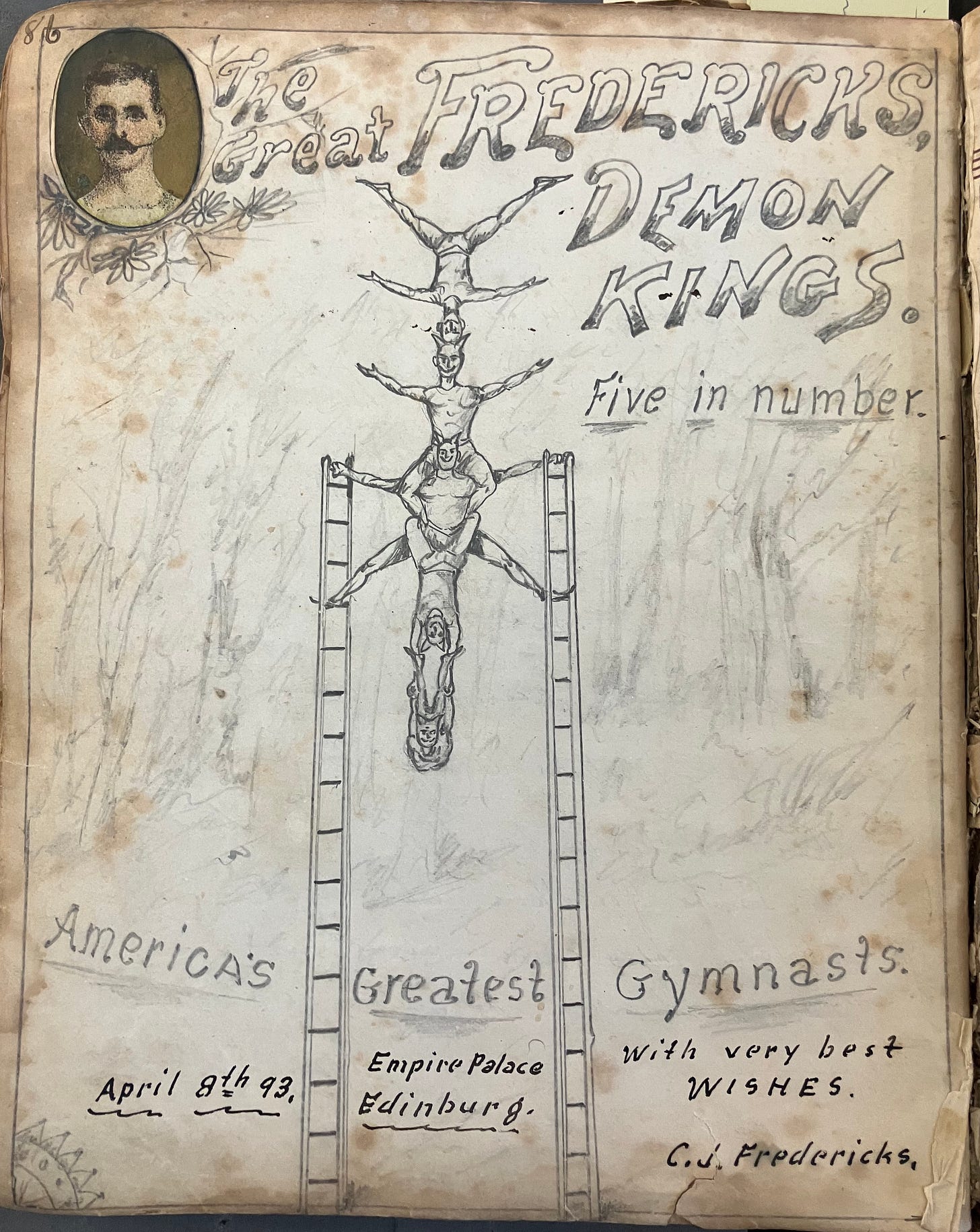

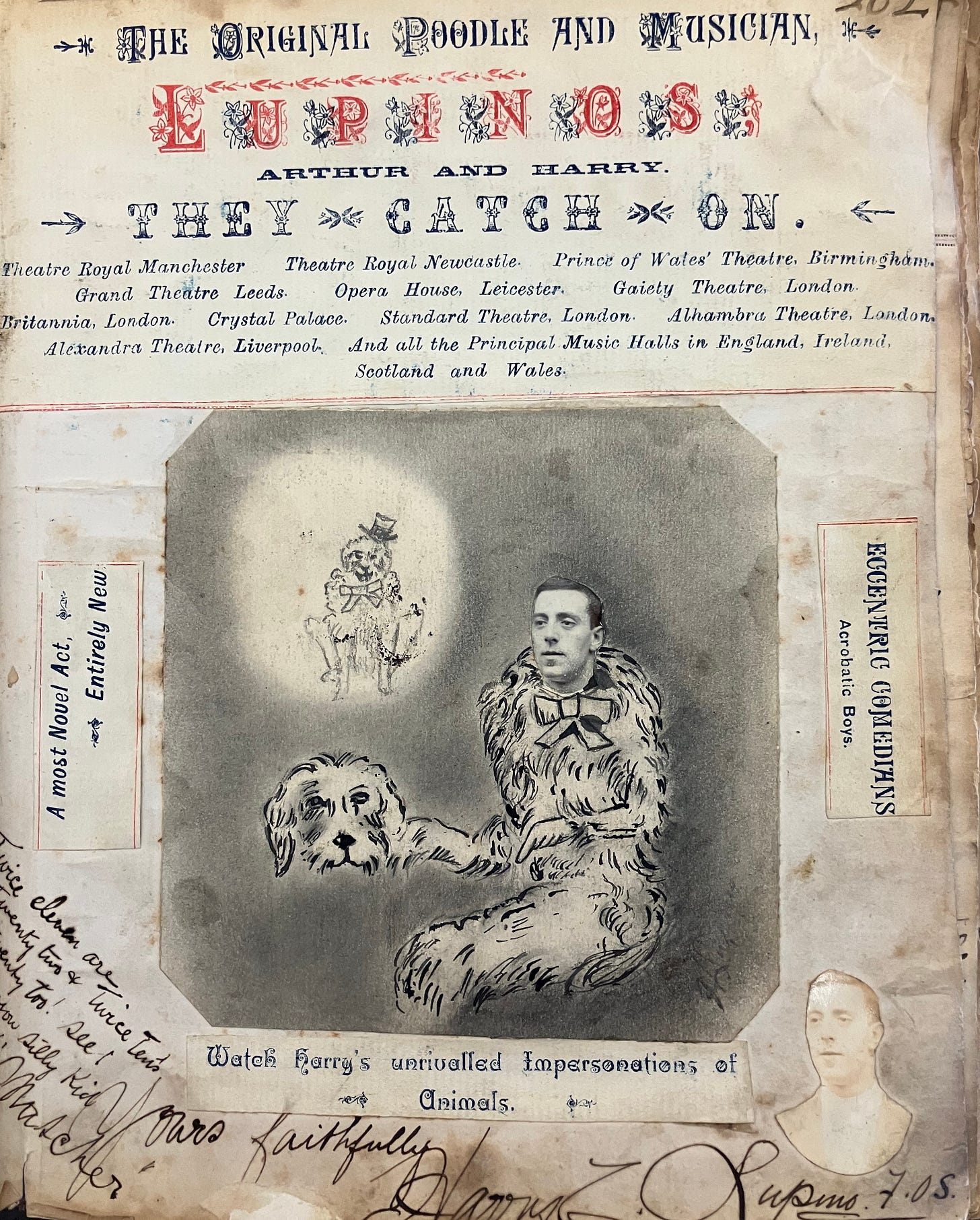

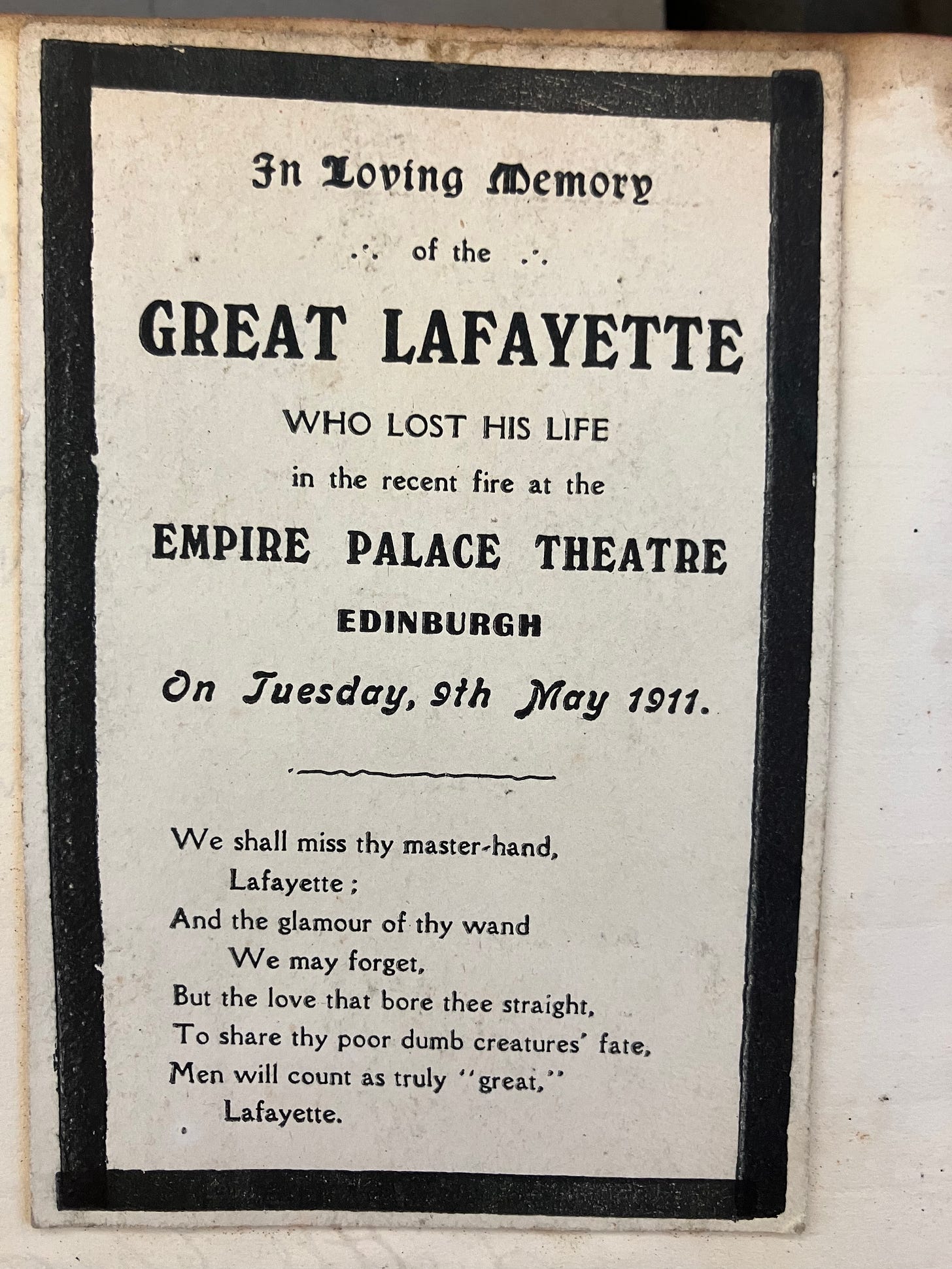

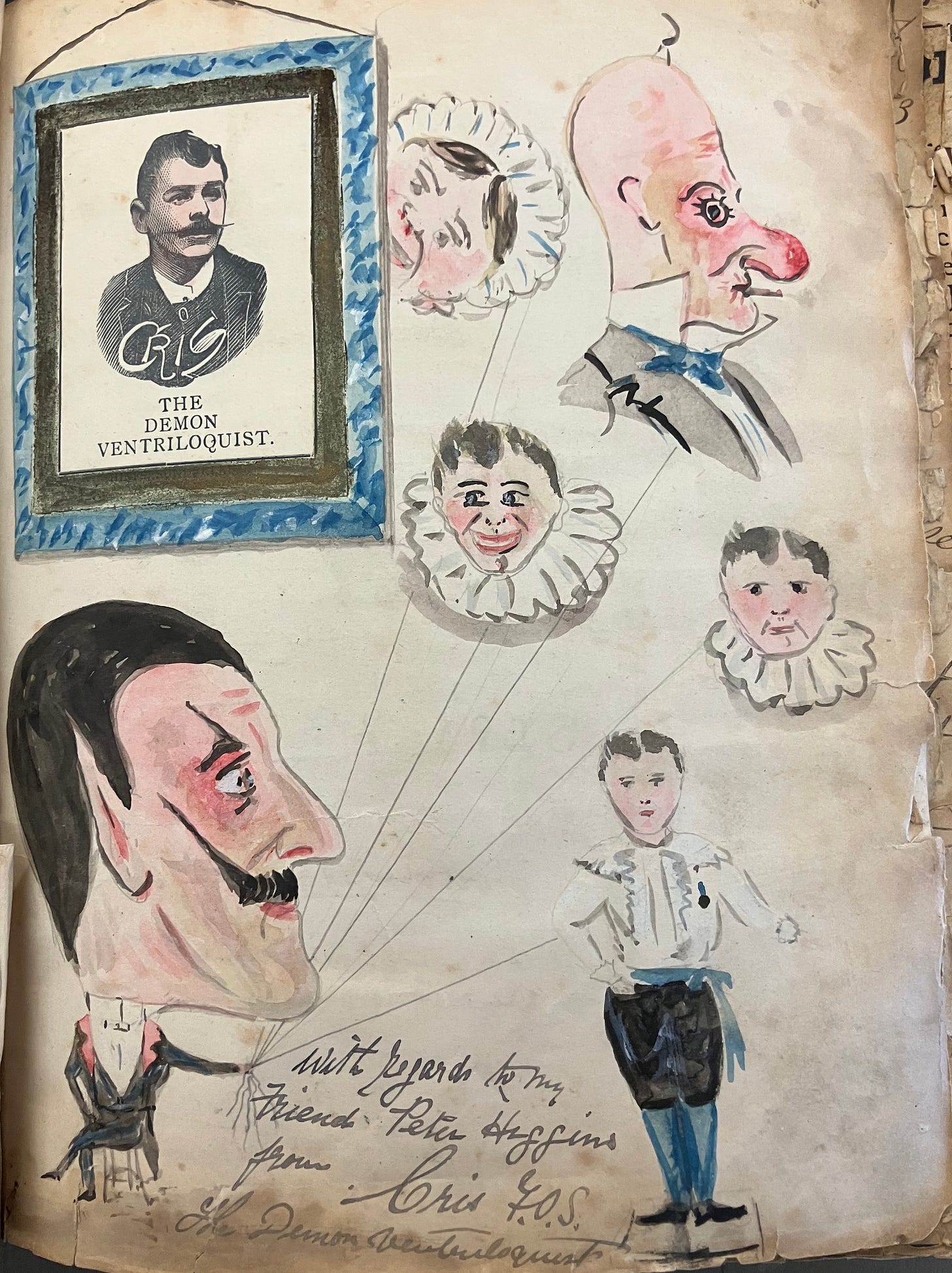

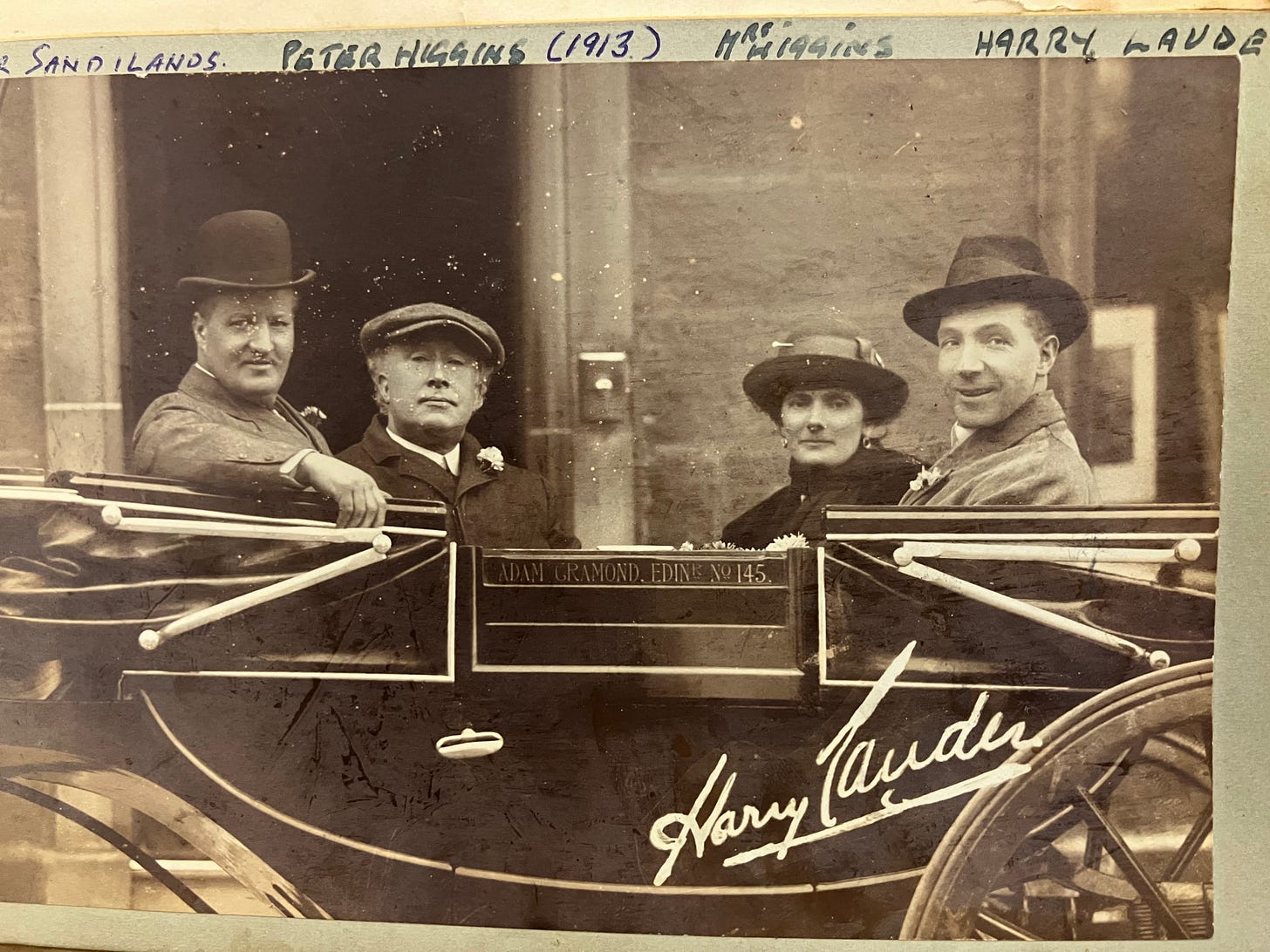

It’s time for some obscure magic and music hall history.

I’m a fan of a remarkable Scottish conjurer called Harry Marvello. He was performing during the early 1900s and built a theatre in Edinburgh that is now an amusement arcade. I have a previous post on Marvello here and have just written a long article about him for a magic history magazine called Gibecière (the issue is out soon).

I am staging a one-off performance of the World’s Most Boring Card Trick at Magic Fest in Edinburgh on the 27th December. Tickets here. Anyway, I digress. I have long been fascinated by the psychology of humour and once carried out a project called LaughLab. Billed as the search for the world’s funniest joke, over 350,000 people submitted their top gags to our website and rated the jokes sent in by others. We ended up with around 40,000 jokes and you can read the winning entry here (there is also a free download of 1000 jokes from the project).

It was a great project and is still quoted by media around the world. I ended up dressing as a giant chicken, interviewing a clown on Freud’s couch, and brain scanning someone listening to jokes.

A few years ago, I came up with a theory about Christmas cracker jokes. They tend to be short and not very funny, and it occurred to me that this is a brilliant idea. Why? Because if the joke’s good but you don’t get a laugh, then it’s your problem. However, if the joke’s bad and you don’t get a laugh, then you can blame your material! So, cracker jokes don’t embarrass anyone. Not only that, but the resulting groan binds people together. I love it when the psychology of everyday life turns out to be more complex and interesting than it first appears! As comedian and musician Victor Borge once said, humour is often the shortest distance between people.

I recently went through the LaughLab database and pulled out some cracker jokes to make your groan and bond:

– What kind of murderer has fibre? A cereal killer.

– What do you call a fly with no wings? A walk.

– What lies on the bottom of the ocean and shakes? A nervous wreck.

– Two cows are in a field. One cow: “moo”. Other cow: “I was going to say that”

– What did the landlord say as he threw Shakespeare out of his pub? “You’re Bard!”

– Two aerials got married. The ceremony was rubbish but the reception was brilliant.

– What do you call a boomerang that doesn’t come back? A stick.

– A skeleton walks into a pub and orders a pint of beer and a mop.

The BBC have just produced an article about it all and were kind enough to interview me about my theory here.

Does the theory resonate with you? What’s your favourite cracker joke?

Have a good break!

Subscribe

Subscribe OPML

OPML