sources

- bad science

- diary of a teenage atheist

- new humanist blog

- pharyngula

- richard dawkins foundation

- sam harris

- skepchick

- richard wiseman

Powered by Perlanet

This morning I started walking to work, and I stepped on some ice and went flying, to fall flat on my back, my neck, and my head. I remember that, and I recall curling into a fetal position, and then somehow magically I had gotten up and walked to the science building, climbed the stairs, and gotten in to my office. I have no memory of walking. But a half hour later I texted my wife, “I might need hospital” and blacked out again. Then she showed up in the office, and then somehow I’m in the emergency room. I kept blacking out.

Lots of tests followed. I was concussed but there was no brain bleed and no broken bones. I’m in serious pain, and my rib cage periodically clenches like a fist, but I’m coping with the aid of tramadol and some other muscle relaxant. I have a note from the doctor to excuse me from work for a few days, but come on, my job is not physically demanding, I think I can power through with the assistance of my wheelchair and a few drugs. Because I’m a stupid macho man.

I’m somehow on this email list called “evolutionary leaders,” which is not what it sounds like. This is an organization led by a gang of New Age weirdos, and I only remain on it for the hilarity. I thought I’d share a little bit of my amusement.

This morning I received an announcement that this is the Year of the Fire Horse.

Why the “fire horse”? They don’t explain. I think they just liked the graphic.

They were announcing an event on February 20, which has historical precedent. They’ve done it before!

In 1987

Thousands gathered in sacred sites for the Harmonic Convergence, ushering in a planetary frequency shift.In 2003

The Harmonic Concordance marked a cosmic alignment of healing and divine feminine resurgence.

You all remember those amazing events with all their wonderful consequences, right? Are you prepared for what will happen on the 20th of February?

Now in 2026

Harmonic Emergence is a planetary activation—an invitation to embody the coherence we’ve long cultivated and step into the living reality that many cultures have prophesied and named throughout centuries: the Unitive Age, The Golden Era, The Age of Aquarius, The Rainbow Prophecy, The Great Turning, The New Dawn, to name a few.Harmonic Emergence completes the triad. It is the moment we stop preparing for the New Earth—and begin living it.

Simultaneously nebulous and dramatic–impressive. In case you want to participate, the instructions are even more vague.

In addition to attending the online global event we encourage you to amplify your impact locally in some way.

Host a circle or meditation with neighbors, friends, family

Gather around a bonfire, river, or sacred site

Create ceremony, blessing the land and waters

Offer poetry, prayer, silence, music, dance

Organize a potluck or celebration of joy, resilience, and emergence

Hold a moment of stillness with others in your town square or backyard

Bring your community into coherence with song or sacred sound

Anchor the transmission in your unique way

The important part, though, is attending the online global event

, which means “sign up for our mailing list which we can monetize.” You could listen to these impressively vacuous people.

The Harmonic Emergence Experience is hosted by the Connection Field, and a luminous circle of musicians, mystics, artists, and planetary stewards—including Jude Currivan, Kristin Hoffmann, Amma Li Grace, Reverend Rhetta Morgan, Julie Krull, Wolf Martinez, Rev. Canon Charles P. Gibbs, Teresa Collins, Marshall Lefferts, Theo Grace, and other ceremonial leaders—this global online experience will be both poetic transmission and living ceremony, holding a field of resonance across time zones.

I think I’ll skip it. It is amazing how little these people will do while claiming to change the world.

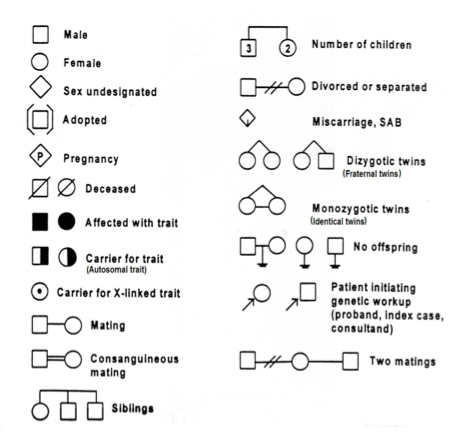

The lesson for today includes an introduction to pedigree analysis. You all know the conventions of a human pedigree, right?

I also include an addendum.

Genetics science is gradually catching up and recognizing that trans people exist, although there is still some confusion about precisely how to acknowledge them.

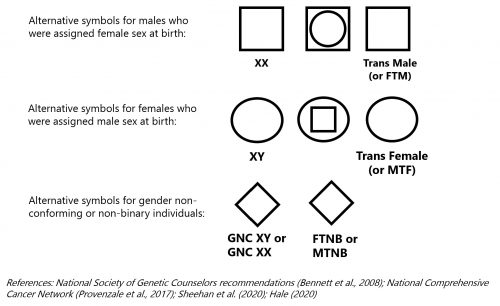

Laura Loomer watched the Superbowl, and revealed so much.

lllegal aliens and Latin hookers twerking at the SuperBowl.

What was the clue that these were “illegal aliens”? Do you have some kind of super-vision that lets you spot people who entered the country illegally? Also, Puerto Ricans are not aliens.

Not a single white person or English translation at the Super Bowl.

Stefani Germanotta (Lady Gaga) was in the show. Pay attention, people of Italian descent — you are no longer white.

This isn’t White enough for me.

That’s an amazing thing to say. You need everything to be White? All mayo and ranch dressing?

Cant even watch a Super Bowl anymore because immigrants have literally ruined everything.

Puerto Ricans are citizens of the United States. How many times does that need to be explained to conservatives?

In some good news, VDARE, the white supremacist organization, has been in its death throes for over a year. Peter Brimelow has resigned, Letitia James has speared them with legal action, “crucifying” the site and leaving it “on life support”. The last articles on the site are from July of 2024 — would you believe John Derbyshire, a name I have not heard in ages, was their most prolific poster? Corruption has killed them, which is always going to be a problem for these kinds of organizations.

Such is the fate of racists. Laura Loomer may have the ear of the president, but she’s just a crank shrieking on Twitter. She’ll be gone soon.

The Seattle Seahawks won the SuperBowl 29-13. Several members of my west coast family were watching and cheering for the home team.

For many of us, the only reason to watch the SuperBowl is the half-time show, and here it is stripped of the surrounding violent game and ads.

I don’t understand the lyrics, but I liked the music and dancing. I also appreciated the representation of Puerto Rican culture, and at the end when he says “God bless America”…and then lists all the countries that are part of the continent of America. Ironically, TPUSA’s alternative half-time show was called the All American Halftime Show

— I don’t think they would have got the point — and Kid Rock screaming over a poorly adjusted cheap sound system was less intelligible than Bad Bunny’s Spanish.

This week we have a quick quiz to test your understanding of sleep and dreaming. Please decide whether each of the following 7 statements are TRUE or FALSE. Here we go….

1) When I am asleep, my brain switches off.

2) I can learn to function well on less sleep.

3) Napping is a sign of laziness.

4) Dreams consist of meaningless thoughts and images.

5) A small amount of alcohol before bedtime improves sleep quality.

6) I can catch up on my lost sleep at the weekend.

7) Eating cheese just before you go to bed gives you nightmares

OK, here are the answers…..

1) When I am asleep, my brain switches off: Nope. When you fall asleep, your sense of self-awareness shuts down, but your brain remains highly active and carries out tasks that are essential for your wellbeing.

2) I can learn to function well on less sleep: Nope. Sleep is a biological need. You can force yourself to sleep less, but you will not be fully rested, and your thoughts, feelings and behaviour will be impaired.

3) Napping is a sign of laziness: Nope. Your circadian rhythm make you sleepy towards the middle of the afternoon, and so napping is natural and makes you more alert, creative, and productive.

4) Dreams consist of meaningless thoughts and images: Nope. During dreaming your brain is often working through your concerns, and so dreams can provide an insight into your worries and help come up with innovative solutions.

5) A small amount of alcohol before bedtime improves sleep quality: Nope. A nightcap can help you to fall asleep, but also causes you to spend less time in restorative deep sleep and having fewer dreams.

6) I can catch up on my lost sleep at the weekend: Nope. When you fail to get enough sleep you develop a sleep debt. Spending more time in bed for a day will help but won’t fully restore you for the coming week.

7) Eating cheese just before you go to bed gives you nightmares: Nope. The British Cheese Board asked 200 volunteers to spend a week eating some cheese before going to sleep and to report their dreams in the morning. None of them had nightmares.

So there we go. They are all myths! How did you score?

A few years ago I wrote Night School – one of the first modern-day books to examined the science behind sleep and dreaming. In a forthcoming blog post I will review some tips and tricks for making the most of the night. Meanwhile, what are your top hints and tips for improving your sleep and learning from your dreams?

Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global (William Collins) by Laura Spinney

In 1786, Sir William Jones, a British philologist and judge, made the remarkable discovery that the ancient Indian language Sanskrit resembled Latin and Greek, “bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident”. So was born the knowledge that has now expanded to recognise almost all of the modern European languages as Indo-European – alongside the main northern Indian languages, and some western Asian ones, such as Farsi.

A book by science journalist Laura Spinney now gives us the background on how the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language was discovered, with linguists ingeniously managing to trace dozens of languages back to construct a hypothetical source language, estimated to have been spoken from 4,500 to 2,500 years ago. Most of the book is taken up with the question of where the language originated, and how it managed to spread so successfully across the globe.

The search for the region that birthed the language had proved elusive, until Svante Pääbo, in 2010, developed the technique of ancient DNA sequencing, for which he won the Nobel Prize in 2022. Originally used to sequence the Neanderthal genome, the work expanded so rapidly, especially in David Reich’s laboratory at Harvard, that in 2015 the renowned British archaeologist Colin Renfrew wrote that “In just five years the study of ancient DNA has transformed our understanding of world prehistory.”

That same year, a paper was published by Reich’s group, imperiously titled “Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe”. This, along with another, similar paper, proclaimed the end of the PIE mystery. The steppe is the vast region of grassland that runs for 5,000 miles from central Europe to Manchuria. The origin of PIE (and hence the languages now spoken by almost half the world’s people) was judged to be the Pontic-Caspian steppe, north of the Black Sea – land that is now part of southern Russia and Ukraine. The population of the steppe, the Yamnaya, were animal-herding, horse-riding and chariot-driving nomads.

However, as Spinney explores, the mystery hasn’t been quite resolved. An earlier theory had proposed that PIE originated in Anatolia, land that now makes up the majority of Turkey – and it turns out that both might be correct. In 2022, Reich and his group showed that there had been an earlier migration from the mountains of Armenia, around 5000 BC, to both the Black Sea and Anatolia. In this theory, one branch of an archaic root language became the Anatolian languages, and another – via the Yamnaya culture – went on to produce the plethora of Indo-European languages.

Spinney shows us why this debate matters to us today. One pressing reason relates to false ideas around racial superiority. Yamnaya is the greatest part of the genetic heritage of most white Europeans (including in North America); English is the world lingua franca today; and from 1492 Europeans colonised a large part of the rest of the world. For some people, the belief that so many of our languages were birthed from the Yamnaya lent spurious credence to the notion that it was natural for white Europeans to conquer other peoples. The Nazis were invested in this idea, falsely locating the Indo-European source in Germany.

But how did the Yamnaya manage to dominate other cultures and impose their language? They were highly mobile nomads, and may have been physically stronger. Spinney writes, they are thought to have been “10 centimetres taller than the male farmers they encountered”. But were they violent conquerors? In Britain around 4,000 years ago the population was 90 per cent replaced by people with Yamnaya genes. But Spinney reports that, as with the British colonists in North America, who carried lethal smallpox (to which they were immune), the cause of the population change might have been infectious disease.

As a story emerges, what are we going to make of our exceedingly murky heritage? These issues are only hinted at in Proto but it is the best source – as up to date as possible – on the fantastic odyssey of our languages and the migrating peoples that carried them.

This article is from New Humanist's Winter 2025 edition. Subscribe now.

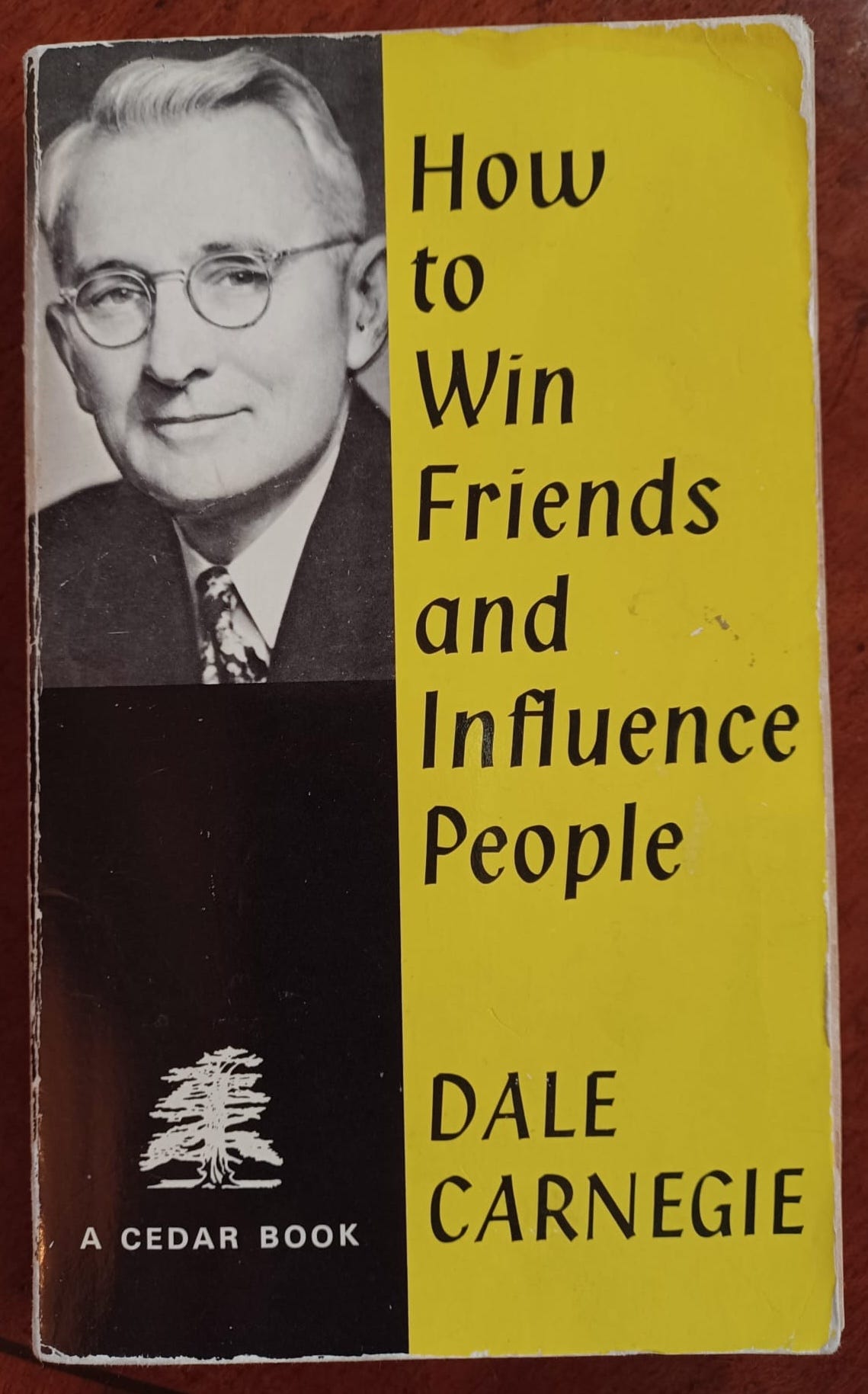

I am a huge fan of Dale Carnegie and mention him in pretty much every interview I give. Carnegie was American, born in 1888, raised on a farm, and wrote one of the greatest self-help books of all time, How to Win Friends and Influence People. The book has now sold over 30 million copies worldwide.

I first came across his work when I was about 10 years old and read this book on showmanship and presentation….

According to Edward Maurice, it’s helpful if magicians are likeable (who knew!), so he recommended that they read Carnegie’s book. I still have my original copy, and it’s covered in my notes and highlights.

One of my favourite — and wonderfully simple — pieces of advice is to smile more. Since the book was written, psychologists have discovered lots about the power of smiling. There is evidence that forcing your face into a smile makes you feel better (known as the facial feedback hypothesis). In addition, it often elicits a smile in return and, in doing so, makes others feel good too. As a result, people enjoy being around you. But, as Carnegie says, it must be a genuine smile, as fake grins look odd and are ineffective. Try it the next time you meet someone, answer the telephone, or open your front door. It makes a real difference.

In another section of the book, Carnegie tells an anecdote about a parent whose son went to university but never replied to their letters. To illustrate the importance of seeing a situation from another person’s point of view, Carnegie advised the parent to write a letter saying that they had enclosed a cheque — but to leave out the cheque. The son replied instantly.

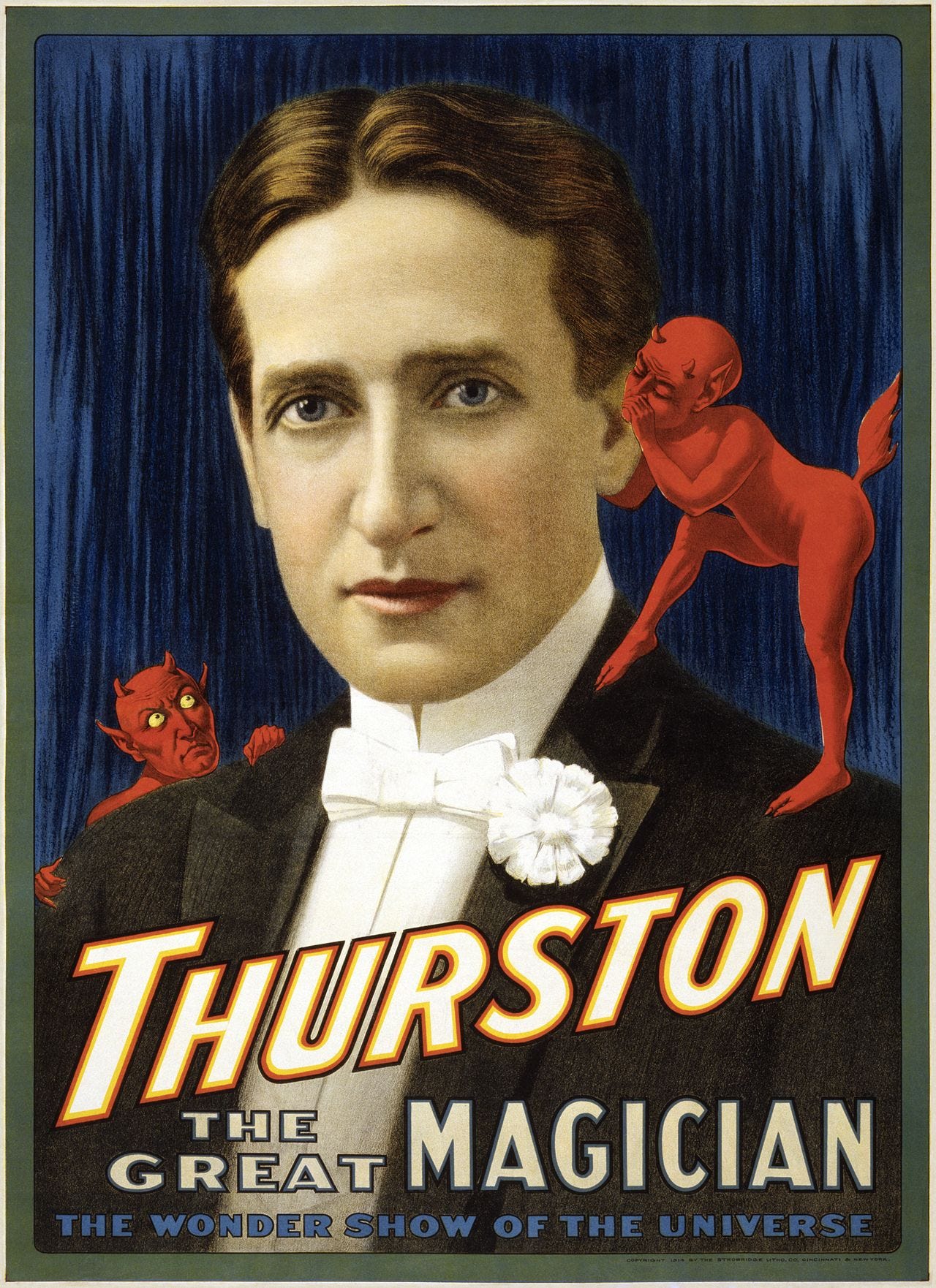

Then there is the power of reminding yourself how much the people in your life mean to you. Carnegie once asked the great stage illusionist Howard Thurston about the secret of his success. Thurston explained that before he walked on stage, he always reminded himself that the audience had been kind enough to come and see him. Standing in the wings, he would repeat the phrase, “I love my audience. I love my audience.” He then walked out into the spotlight with a smile on his face and a spring in his step.

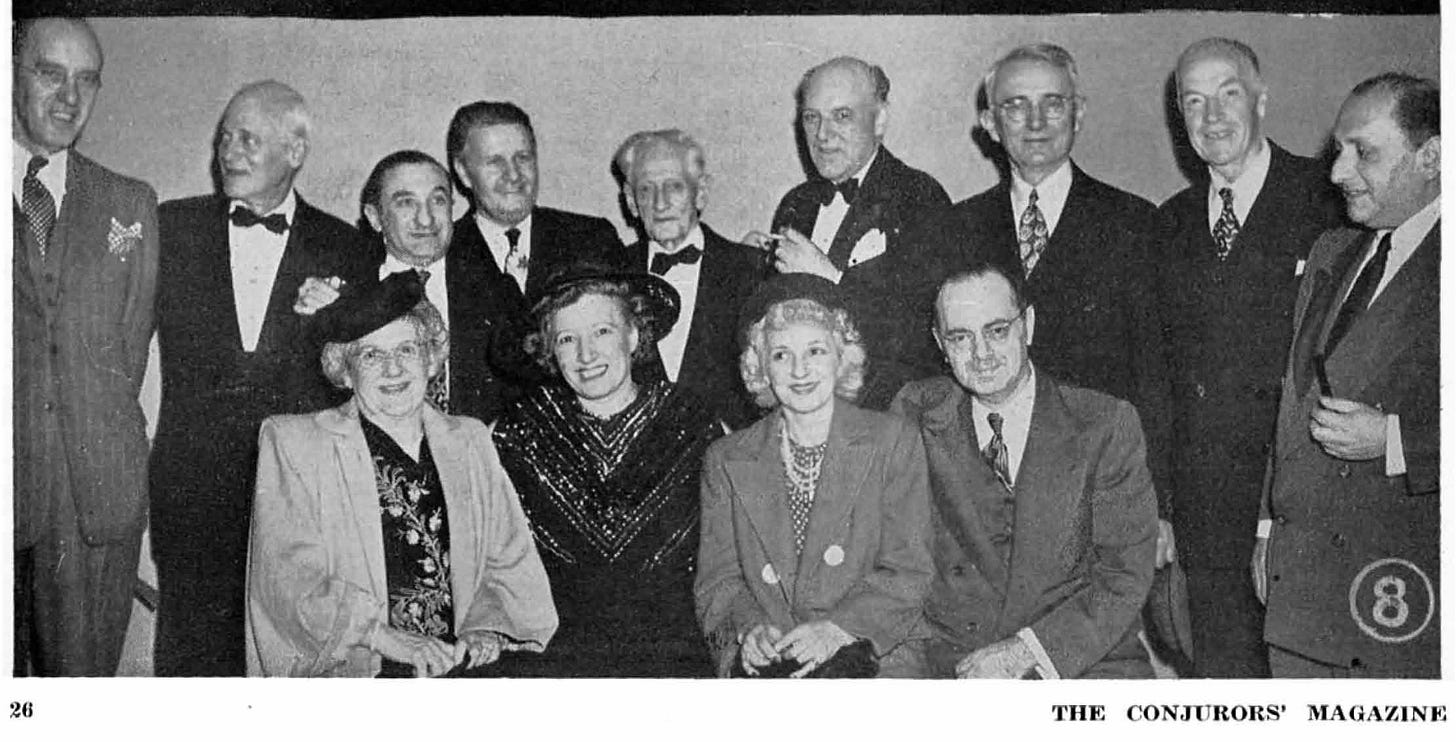

This is not the only link between Carnegie and magic. Dai Vernon was a hugely influential exponent of close-up magic and, in his early days, billed himself as Dale Vernon because of the success of Dale Carnegie (The Vernon Touch, Genii, April 1973). In addition, in 1947 Carnegie was a VIP guest at the Magicians’ Guild Banquet Show in New York. Here is a rare photo of the great author standing with several famous magicians of the day (from Conjurers Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 4; courtesy of the brilliant Lybrary.com).

Front row (left to right): Elsie Hardeen, Dell O’Dell, Gladys Hardeen, J. J. Proskauer

Back row: E. W. Dart, Terry Lynn, Al Flosso, Mickey MacDougall, Al Baker, Warren Simms, Dale Carnegie, Max Holden, Jacob Daley

If you don’t have a copy, go and get How to Win Friends and Influence People. Some of the language is dated now, but the thinking is still excellent. Oh, and there is an excellent biography of Carnegie by Steven Watts here.

“Let us compare our consciousness to a sheet of water of some depth. Then the distinctly conscious ideas are merely the surface; on the other hand, the mass of the water is the indistinct, the feelings, the after-sensation of perceptions and intuitions and what is experienced in general, mingled with the disposition of our own will that is the kernel of our inner nature.”

– Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation

For many of us today, it is commonplace to talk about the “unconscious”. We might use it to explain our own behaviour, or that of others, or try to uncover its secrets in therapy. We convince ourselves that a friend who finds a new partner soon after a breakup is “on the rebound” – we know their motivations better than they do, we think. Perhaps we ourselves struggle with relationships, and believe this is due to something that happened in our childhood, rather than that we have not yet met someone who makes us want to commit. Our moods, our hopes, our actions, are ascribed again and again to hidden impulses.

The unconscious is not a new idea. It was of course given huge impetus by the work of Sigmund Freud in the early 20th century, but the waning of his influence has had little effect on what we might call his cultural – we might even say “pop-cultural” – influence. From Freudian slips to the search for secret motivations, his ideas are now embedded in the way we talk and live. But there is no hard evidence for the existence of something called “the unconscious”. Is the idea just a way of removing blame from ourselves, and placing it elsewhere?

A brief history of the 'unconscious'

In the late 18th century, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant produced his masterwork, The Critique of Pure Reason. In it, he put forward a theory of mind which, for the most part, claims that all cognition is conceptual – that is, conscious. According to Kant, we are – or can be, if we take the time to reflect – fully self-aware, and can proceed by reason. As a founding text of modern philosophy, Kant’s theory has remained incredibly influential. But in the eyes of many philosophers, he left something crucial out of his picture of the human mind – what his contemporary Friedrich Schelling named “the unconscious”.

We might think the idea is uncontroversial. There are, of course, many things of which our brain is unconscious, even when they are being processed. If we were conscious of every sound around us, or everything within our field of vision, we would be overwhelmed – our brain is constantly filtering these things for us. But this is not what Schelling meant by the unconscious – the above examples are better described as nonconscious. For Schelling, the unconscious was not simply the passive activities of a brain (while thinking about other things), but an active and dynamic component of mind – it influences consciousness.

Arthur Schopenhauer took the idea further. In his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation, not only is consciousness not the whole story of mind, it is merely the surface. For Schopenhauer, the active force of the universe was what he termed “Will”. The whole of the phenomenal world – that which we can see, touch, smell, which we can apprehend rationally and so on – is actually the manifestation of a huge irrational and impersonal drive. This is also the condition of each individual. While we believe our thoughts and motivations are explicable through rational thought, we are deluded. Rather: “The intellect remains so much excluded from the real resolutions and secret decisions of its own will that sometimes it can only get to know them, like those of a stranger, by spying out and taking unawares; and it must surprise the will in the act of expressing itself, in order merely to discover its real intentions.”

In fact, Schopenhauer was sceptical that we can ever get to know our secret decisions. We can only get at the representations of the truth of the universe, and the truths of ourselves. In this he was heavily influenced by Indian philosophy.

In works such as the sacred canonical text of Hinduism, the Rig Veda, dating from at least 3,000 years ago, Schopenhauer’s theory of the world and the mind finds an early parallel, which he was quick to acknowledge. The phenomenal world is, in the Veda, an illusion, with true reality lying behind it – whether we can pull back the veil remains a matter for debate. Similarly, our human self is, in some key sense, ultimately unknowable to itself.

The three 'Master's of Suspicion'

One of Schopenhauer’s great followers – and, later, great critics – Friedrich Nietzsche, is often credited as Freud’s most immediate precursor. As with so much of Nietzsche, his position regarding the unconscious is difficult to pin down. But it remains fascinating. He wanted to question Kant’s idea that we were in control of our chain of thoughts: that when a person goes from thought A to B to C, that is because A led logically to B, which led logically to C. This, to Nietzsche, is to use a current term, “retrofitting” what is actually occurring – finding logical links where none exist. Rather, he argued that “the events which are actually linked play out beneath our consciousness: the emerging sequence and one-after-the-other of feelings, thoughts, etc., are symptoms of the actual event!” The “actual event” is what has happened beneath our thinking, in our unconscious.

In fact, the later French thinker Paul Ricoeur identified Nietzsche as one of what he famously called “the Masters of Suspicion”, each of whom called into question human confidence in our own self-knowledge. The second for Ricoeur was Karl Marx, who saw our minds as created not from within, but out of the social fabric which surrounds us. The third of the three Masters was Sigmund Freud.

Born in 1856, Freud, while being an avid reader of philosophy, trained in medicine before branching off into the field of psychology, establishing his own practice in 1886. While “psychology” as the study of the workings of the mind has been around since the Greeks, the late 19th century saw a great flowering of the discipline, and the Freudian unconscious grew out of a number of similar ideas that were being debated at the time.

Two immediate predecessors were the French psychologists Jean-Martin Charcot and Pierre Janet. Charcot was making groundbreaking discoveries in understanding and treating hysteria, which included the use of hypnosis, while Janet was among the first thinkers to directly link patients’ present conditions to past traumas – in particular traumas which the sufferer had forgotten, or where they were not themselves conscious of a link.

Janet termed this breaking of the link between the trauma and the later symptoms “dissociation”, and placed responsibility in what he called the “subconscious”. Failing to integrate these traumatic experiences with normal selfhood led, he believed, to neurosis. Like Charcot, he used hypnosis, seeing what he called a “magnetic rapport” between the hypnotist and their patient, which allowed for a cure to be performed. This is close to the Freudian model, with hypnosis replaced by “the talking cure”, and the magic rapport being termed “transference”.

Freud's 'internal censor'

But Freud did not just draw on philosophy and psychology as he moved towards his own version of the unconscious. An acute reader of literature, he credited writers such as Shakespeare and Dostoevsky with leading him to theories of unconscious motivation, while of course, his famous – or infamous – concept of the Oedipus Complex is drawn from Greek drama.

There was also his religion. As the French writer Clémence Boulouque analyses in her excellent new book, On the Edge of the Abyss: The Jewish Unconscious Before Freud, the Jewish tradition, both religious and secular, has a strong tradition of engagement with the unconscious – from early works of mysticism and Kabbalism (with their beliefs in an underlying reality generally inaccessible to human understanding) through to the work of Schelling himself, who drew on these traditions. While Freud grew more and more to argue that religion is something to be overcome – in his The Future of an Illusion, religion is the illusion – his work remains peppered with religious symbolism.

For all that, Freud’s version of the unconscious is a more unequivocal one than anything that had preceded it. The unconscious is not, as in Schelling’s understanding, just a place where we store various random parts of our memory and experiences, nor just where we store things we believe we have forgotten.

The unconscious that Freud engages with is one where nothing is random, where nothing psychologically unimportant is stored. It is, specifically, a place formed of our repressed traumas. We have, according to Freud, an “internal censor” that is, in some sense, protecting us from harmful thoughts, by forcing them into the unconscious.

What is crucial here is that, for Freud as for Janet, the unconscious is formed by what happens to us. While Schopenhauer’s version of the unconscious can be criticised for being so impersonal that our individual lives become meaningless (to which criticism Schopenhauer, the great pessimist, might have simply said, “Yup”), for Freud the unconscious is perhaps more personal to us than the selves our conscious thoughts make us believe we are. While some of the behaviours caused by the unconscious of person A might give us clues as to the case of person B, our traumas are deeply individual.

Where, who and what is the 'unconscious'?

Fast forward to the 21st century and, despite criticism of his work, Freud’s ideas on the unconscious have, as we have seen, proved influential on popular beliefs around the workings of the mind, not forgetting the fields of psychotherapy and therapeutic practice. However, the very concept of the unconscious remains a problematic one. Many question whether there is such a thing, and if the idea is even comprehensible.

There is of course the question of location – where is the unconscious exactly? – but this mirrors the question of where consciousness is. Others have raised the question of what it means for Freud (and any psychoanalyst) to “know” about something that is, by its own definition, unknowable.

Further, what sort of game is our internal censor playing that it would hide information from us, and then not only leave clues for us as to its existence (such as, in Freud’s case, slips of the tongue or dream symbols), but also allow us enough access to un-censor the material in some way? And in a way that is good for us – why bother to censor it in the first place? What even is an “internal censor”? Is it part of the mind, too? How? Or we might even ask, “Who?”

This is a version of the homunculus fallacy, where there is a person inside a person inside a person. One thinker to raise it was Jean-Paul Sartre. If “we” are censoring material to keep it away from consciousness, how is that happening? Do we have another consciousness inside us – a little person or homunculus – which knows what is or isn’t acceptable, then makes a decision? But wouldn’t they need another one inside them, like a Russian doll? Finally, how is what is to be censored decided?

A bid to evade responsibility?

Sartre, for whom personal responsibility is paramount, thought the idea of the unconscious was the product of the human desire to evade responsibility. Rather than blaming ourselves for any wrongdoing, we are able to pass on the blame to our unconscious, and then, through psychoanalysis, on to those who have shaped it – our parents, for example.

This is Sartre joining the dots between the gods of the Greeks, the primal Will of Schopenhauer or Nietzsche, and the unconscious of Freud – they are all of them, in his belief, mythical beasts which allow us to evade culpability. As the first humans invented gods to hold responsible for the great mysteries, so have we, but placed them inside us.

This is not to say that Sartre dismissed Freud’s work entirely. In fact he attempted to create a psychoanalysis aligned to Freud’s – just without the unconscious. This he termed existentialist psychoanalysis. He too believed we were shaped by external forces, but there was no extra layer of repression and censoring which needed to be accounted for.

While he admitted, with Nietzsche, that our motivations and indeed our consciousness might be opaque, opacity does not mean something inside us is performing an act of mysticism. Chinese mathematics is opaque, but it can be learnt. As a contemporary of Sartre’s, Eric Fromm, put it:

“The term ‘the unconscious’ is actually a mystification … There is no such thing as the unconscious; there are only experiences of which we are aware, and others of which we are not aware, that is, of which we are unconscious. If I hate a man because I am afraid of him, and if I am aware of my hate but not of my fear, we may say that my hate is conscious and that my fear is unconscious; still my fear does not lie in that mysterious place: ‘the’ unconscious.”

Sartre’s argument is also one against determinism. Given facts A, B and C, Freud seems to suggest in this account, we will have outcome D. Freud believes he can argue, for instance, that a person behaves in a certain way because of this or that childhood trauma. Determinism was anathema to Sartre – we must, in his philosophy, have the ability to shape our own ends.

So, where does this lead us, when we reflect on the workings of our own minds, and the minds of others? We might like to think, as Kant did, that we are entirely rationalist thinkers, or as Sartre did, that we have absolute responsibility. But many of us still speak of, and believe in, the existence of the unconscious. It’s a belief that predates Freud and will undoubtedly continue in different forms for as long as humans try to pin down the self. Much of our burgeoning therapeutic industry relies on the idea, so it’s easy to forget that it is contested.

As Shakespeare has Hamlet say, “There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in your philosophy.” The sheer amount of “life” to which we are all exposed makes consciousness seem a thin tool for apprehending it. Perhaps science is not the place to seek the unconscious. Perhaps, like god, the unconscious may simply be a powerful metaphor – one that helps us understand and deal with our experience – rather than a thing?

This article is from New Humanist's Winter 2025 edition. Subscribe now.

A Different Kind of Power: A Memoir (Macmillan) by Jacinda Ardern

Jacinda Ardern was the 40th prime minister of New Zealand, but the first to become an internationally recognised figure – certainly, Keith Holyoake and Robert Muldoon never appeared on the cover of Vogue. Ardern became an instant object of fascination because – at least when measured against her fellow national leaders, an overwhelmingly male, middle-aged-and-upwards and mostly somewhat dreary cohort – she seemed different: a 37-year-old woman of generally cheerful demeanour. As the title of her book suggests, Ardern also sees herself as different, in substance as well as style.

Ardern is, at the very least, a different kind of political memoirist. A Different Kind of Power is short on wearisome policy minutiae, and petulant score-settling. The book’s strength is that it depicts, very capably, the human experience of national leadership – its pressures and dilemmas, its drama and slapstick, its gravity and absurdity. The prologue captures the moment amidst the post-election negotiations which brought her to power in 2017 when Ardern discovers she is pregnant.

After which, Ardern starts at the start: her childhood in small rural towns where her father served as a police officer. Ardern clearly believes this was the making of her: the conscientious, empathetic child becoming a prime minister of similar qualities (if the book has one minor but recurring fault, it is an over-emphasis on the “if anything, I just care too much” schtick).

Ardern grows up a Mormon, but drifts from the church in her twenties. It is always illuminating to discover why people reject the faith in which they are raised. It is not an easy call, risking as it does the ostracism of family, friends and community.

Her departure from the Church of Latter-Day Saints is admirable in motivation and execution. She reaches a point at which she cannot accommodate both her belief in equal rights for gay people and the LDS’s institutional animus towards them – but she moves on without bitterness, while maintaining admiration for the good the Mormons do, and the good people among them. She also drily notes that the experience of knocking on strangers’ doors, trying to interest them in new ideas while they’re trying to eat dinner or watch the match, is excellent practice for becoming a campaigning politician.

The most gripping sections of A Different Kind of Power are those that recall the two worst moments of her premiership – neither of which any incoming prime minister of New Zealand would have imagined likely. One was the predicament that confronted everybody in a job like hers in 2020. Though Covid-19 menaced New Zealand less than it did most countries – far-flung islands had a considerable advantage – its prime minister still faced excruciating choices. “For each decision we made,” Ardern writes, “hundreds of new ones presented themselves.” This summary of the infernal complexity of politics would be lost, regrettably, on the sorry mobs of social media-addled bozos who besieged New Zealand’s parliament, having convinced themselves that they were subjects of a tyranny, as opposed to the supernaturally fortunate citizens of a lavishly blessed nation. (“At one point,” Ardern deadpans, “I even saw the glint of literal tinfoil hats.”)

The other defining crisis of Ardern’s term was the terror attack on two mosques in Christchurch in 2019, in which 51 people were murdered and dozens more injured, by a lone maniac. Ardern deserved the plaudits she received for her calm and thoughtful leadership in the hours and days immediately following this atrocity, but as she tells it here, her initial reaction was less composed. “All of the confusion and frustration I felt,” she writes, “turned into one singular emotion: blinding rage.” A pertinent reminder that despite the perennial voters’ complaint about politicians not saying what they actually think, there are times when it really wouldn’t be helpful, or appropriate.

When Ardern stepped down in 2023, citing exhaustion, cynics claimed that her polling ahead of that year’s election may have been more of a factor. She was, by this time, one of those leaders vastly more popular abroad than at home, and her Labour Party were duly clobbered. But if she was tired, she was entitled to be. The great service A Different Kind of Power performs is that it reminds us that politicians are people – people to whom we give impossible jobs, and of whom we demand impossible results.

This article is from New Humanist's Winter 2025 edition. Subscribe now.

In We, a dystopian fable written in 1921-22 and set in the 26th century, the Russian author Yevgeny Zamyatin imagined a totalitarian regime called “OneState”. The buildings in this urban civilisation are uniformly constructed out of clear glass bricks, through which the sinister “Guardians”, its law enforcers, can monitor their subjects’ every move. As the automaton-like protagonist, D-503, puts it, “We live in broad daylight inside these walls that seem to have been fashioned out of bright air, always on view.” The use of glass is thus a key component of the state’s attempt to annihilate the individual personality in the machine-like collective. Zamyatin’s vision would influence George Orwell’s 1984.

At the turn of the 20th century, the introduction of machines that could manufacture large-scale flat glass led to the increasing use of glass in architecture – for better or worse. Among the vitro-optimists was Paul Scheerbart, an eccentric German writer and critic who produced both a treatise and a novel on the potential of glass architecture. The novel, entitled The Gray Cloth and Ten Per Cent White (1914), imagined a fantastical mid-20th-century society in which superstar architects travelled around the globe in airships, admiring their colossal buildings of coloured glass.

A century after Zamyatin and Scheerbart, glass has, to an extent unprecedented in human history, become ubiquitous not only in architecture but in technology, industry and daily life. Indeed, 2022 was the United Nations International Year of Glass. The official booklet proclaimed a new Glass Age and highlighted the material’s importance in areas including communications, biomaterials, energy generation, sustainability, healthcare and aerospace.

Despite its topicality, however, there is one field in which glass remains undervalued: contemporary art. Artists who work mainly in glass, especially if they actually handle the material themselves, have trouble getting their pieces accepted by the art world. “Glass is usually perceived as a traditional material for craft rather than for fine art galleries,” says Marieta Tedenac, a Prague-based conceptual artist who works in glass and other media.

This sort of attitude perhaps says more about the art world than it does about glass. Be that as it may, in the last few decades several artists, whether working alone or collaboratively, have laboured to demonstrate the potential of glass as an artistic medium – a means of free creative expression – and one which benefits from a combination of imaginative vision and inspiration, scientific and technical knowledge, and painstaking, skilful craftsmanship. Arguably, their achievements show that art in glass has a distinctive contribution to make to our uniquely glassy age.

Glass is certainly important for the digital world and Big Tech, most visibly through its use in computer and smartphone screens. This importance is reflected in the glass-heavy architecture adopted, for instance, in Apple stores. In 2013-14, Google even tried, unsuccessfully, to trademark the word “Glass” in a particular font for its “smart glasses”. It is thus surely significant that when Apple wanted to commission a public artwork for the Apple Park outside its headquarters in Cupertino, California, the proposal it selected in 2021, submitted by the Scottish conceptual artist Katie Paterson and the architectural studio Zeller & Moye, was made of glass.

Completed in 2023, Mirage is an installation of 448 glass columns, each standing two metres tall and weighing 90kg, and varying in colour from deep green to mineral blue to near-transparent. It represents a monumental collaboration involving artist, architects, Apple staff, scientists and glassmakers, as well as sand sourced from 70 deserts around the world. The columns are arranged in a pattern of three wavy lines, which, from a drone’s-eye view, suggest “desert dunes”, according to the creators – or, on a more subversive interpretation, a pixellated corporate logo.

Mirage is full of ambivalence, ostensibly being constructed for the benefit of Cupertino’s citizens, but redolent, beneath the glittering surface, of Apple’s apparent ambitions for technological supremacy – in which glass plays an essential role.

One specific type of glass that has been used effectively in art is optical glass. Made with a range of specialised chemical compositions, it was originally developed for lenses and prisms, including in a military context, which needed to refract light precisely. In the 1960s, Václav Cigler, a leading Czech artist and founder of the Glass in Architecture department at Bratislava University, began experimenting with optical glass. He designed sculptures that were precisely cut, ground and polished to achieve brilliantly reflective surfaces. His pure, minimalist forms – an egg, a pyramid, a cone – distil the essence of shapes found in nature and architecture, functioning as almost mathematical focal points which encourage detached contemplation.

One of the reasons that the art world is suspicious of glass art may be the technical challenges involved in its creation. Some contemporary artists have an awkward relationship with the act of “fabricating” (or making) artworks, following current wisdom that what matters is choosing the material that best suits what the artist wants to say, rather than one that he or she has the most skill in manipulating. Yet this attitude may itself owe something to advances in digital technologies such as graphics, 3D printing and generative AI, compared to which, these days, a human’s ability to make things can seem less impressive. Not only are machines better at fabricating, but the virtual world has become ever more sophisticated and enticing. Why bother to make anything that will be subject to the laws of nature, when you could conjure up impossible objects on the screen?

Last year, Luca Curci Architects, an Italian firm, published the “Floating Glass Museum” project on its website. This quixotic museum, designed with the aid of AI, takes the form of a curved white building with fluorescent panes of glass that floats on a swimming-pool-like sea. Inside are rooms filled with large numbers of huge glass spheres. Some of the spheres even seem to float above the ground, in defiance of gravity – which AI had apparently not quite grasped at the time. It is pretty to look at, and yet the very ease with which scenarios like this can be produced, once the limitations of the empirical world are removed, arguably makes them less interesting.

To return to “reality”, the paradox of glass is that on the one hand it is so elusive, but on the other so tactile, heavy and difficult to handle. Glass can be shattered, even on a smartphone, and be transformed instantly from something smooth and self-effacing into something sharp and destructive that also does violence to the image within it. No wonder the breaking of a mirror has traditionally been associated with bad luck.

An example of an evocative aesthetic effect derived from breaking glass occurs in the 2022 film The Glass Onion, in which, in a climactic scene, the collection of clear glass sculptures belonging to a villainous tech entrepreneur is smashed by his guests – as though the sculptures’ entire raison d’être was their destruction.

The brittleness of glass, the risk of chipping or breakage that could annihilate a work’s perfection in an instant, doubtless contributes to its perception as a challenging, even off-putting artistic medium. On the other hand, this same quality can be used as a metaphor to express contemporary concerns. One example is in Stampede, a collection of clear glass animal paws, hot-sculpted by the New York-based artist Deborah Czeresko. The sculptures are carefully modelled on real paws, both live and stuffed, and include a range of species – bat, camel, mole, ostrich, platypus, penguin. With silent eloquence, the fragility of the material, together with its phantom-like transparency, reminds us of the ease with which animal species may be destroyed. Once gone, it would be as impossible to bring them back to life as to reconstitute a shattered glass paw from its fragments – which, since glass is an amorphous solid, will always be irregular and chaotic.

The rich versatility of glass, both as material and as store of imagery, is further exemplified in the work of the American artist Jon Kuhn, who makes sculptures in the form of geometrical solids containing hundreds of facets of glass that refract the light from within like tiny prisms. He does this by a time-consuming process of cutting and polishing segments of optical glass and then laminating them together in a complex structure.

It is a piece by Kuhn, if I am not mistaken, that appears on a table just behind the eminent philosopher and public intellectual Martha Nussbaum, in a photograph taken in 2017 and published alongside an interview in the New York Review of Books in 2021. The positioning creates a connection between the jewel-like interior of the glass and the clarity and sparkle of the sitter’s mind.

As the work of artists like Cigler, Czeresko or Paterson shows, in our new Glass Age, this material can no longer be dismissed as old-fashioned or suitable merely for craft. Instead, it can be an eloquent means of imaginative creation and self-expression.

In a world where our attention is increasingly occupied by images and events behind the glass screen, the material from which that screen is made, with its combination of smoothness and sharpness, liquidity and solidity, depth and surface, can remind us of how dependent we are, despite ourselves, on physical things.

It can thus function as an empirical and metaphorical barrier – the modern equivalent of a looking-glass – between the digital realm and our own. Finally, a key function of art in our image-conscious age is as status symbol and personality extension. In this respect, while some artists may still dismiss it as a medium, glass can surely give bananas, Lego bricks or even paintings a run for their money.

This article is from New Humanist's Winter 2025 edition. Subscribe now.

In February 2024, people across the US began placing orders for a plant that glows at night. The Firefly Petunia, sold by the synthetic biology startup Light Bio, looks like a regular white petunia by day – but in darkness it transforms, emitting a soft light, most visible in its flower buds. The first glowing plant was created in 1986, but it has taken 38 years for the technology to be enjoyed in people’s homes and offices.

Most people are interested in the beauty and novelty of the flower. But while the glowing petunias are aesthetically remarkable, they also demonstrate that “living light”, as it’s often called, can move beyond the lab into everyday environments. Most promisingly, bioluminescent and fluorescent plants have practical uses in agriculture. The light the plants emit can help us understand and combat complex threats to crops – including rot, pests and fungal disease – which are likely to deepen with the ongoing climate crisis.

Most of us have seen some instance of bioluminescence, which is defined as light made by living things, and occurs naturally in fungi and animals. Fireflies are the most obvious example, as well as deep-sea creatures and a handful of glowing fungi. The chemistry is straightforward enough: enzymes called luciferases act on small molecules called luciferins (sometimes with cofactors like ATP, an energy-carrying molecule), in the presence of oxygen. The reaction then releases energy as photons.

Fungi and animals have evolved to glow naturally for a variety of reasons. Fireflies emit light to attract mates and warn predators that they’re an unpleasant meal. It’s thought that the deep-sea lanternfish glows in order to blend in with the blue of the sea and avoid predators. In the case of fungi, however, scientists are still speculating. The leading theory is that the glow attracts insects, aiding reproduction and dispersal, which might be especially helpful in dark forest environments.

But plants don’t glow naturally; they never had to evolve that way. We humans have intervened. So how did we engineer these plants, and why?

The science of bioluminescence

The first glowing plants in the 1980s were only suitable for lab environments, and were mostly designed to study genetic processes. Bioluminescence can be used to provide a real-time indicator of plant development and stress response – all without harming the organism. Keith Wood, now chief executive of Light Bio, worked with the team that created the first glowing plant, by inserting a firefly bioluminescent system into a tobacco plant.

Bioluminescent systems from various insects, marine life and fungi can be inserted into plants, but there are important differences in how this is done and how it affects the glow. In some cases, scientists insert just the genes for luciferase, the enzyme that produces light when it reacts with luciferin, or introduce the luciferin chemically along with luciferase. This approach can make the plants glow, but the light usually lasts for a limited time, since luciferin is not produced inside the plant and must be replenished externally.

The next step, then, was to engineer plants to glow throughout their life. This involved designing plants to produce both luciferase and luciferin themselves by inserting the full set of fungal bioluminescent genes. Because these fungal systems use caffeic acid, which plants naturally produce, the engineered plants can run this light-producing reaction autonomously without needing outside chemicals, creating a sustainable, self-sufficient bioluminescent system. But the light emitted was still too weak and unstable for conditions outside the lab.

More recent work has adapted the mushroom genes so that they function better in plant cells and tissues, boosting brightness by up to a hundredfold.

Today, Light Bio focuses primarily on producing ornamental plants. “People are not only excited and surprised when they see a living plant glow in the dark, they’re often deeply moved,” Wood tells me. But the same technology has practical applications outside the lab.

It is being used, for example, in food safety contexts. Quality-control tests use enzymes and chemicals to help detect contamination in milk and meat. These tests measure the presence of ATP, which reacts with the luciferase added to the food products, triggering the chemical reaction that produces light. The amount of light generated is proportional to the level of ATP, which then shows the extent of contamination.

What about using glowing plants in agriculture? One avenue of exploration relates to pollination. Some researchers speculate that glowing cues might affect insect behaviour. For example, a faint bioluminescent cue at dusk might help nocturnal insects such as moths, which rely on colour and shape, to find flowers. Even adult fireflies, themselves pollinators, could be drawn to these flowers at night. If pollination can be encouraged, then this benefits farmers because it can lead to better fruit and seed development, resulting in improved crop yields. But this idea needs more testing outside the labs, with real crops and in real weather, with attention to the ecological side-effects.

The power of fluorescent plants

For now, another kind of light-emission is yielding more concrete benefits for farmers: fluorescent plants. Like bioluminescence, fluorescence also makes living things emit light, but it can’t operate in the dark. A molecule absorbs incoming light and then re‑emits it at a specific wavelength. With the right illumination and filters, the signal answers back. In practice, this usually means using artificial light sources and optical sensors, since ambient sunlight alone is rarely enough to give a clear reading. In short, bioluminescence shines by itself, while fluorescence shines when asked.

The Californian biotechnology company InnerPlant engineers crops to fluoresce in patterns designed to be read with specialised optics, from the ground and from aircraft. Their commercial product is focused on fungal infections in soybeans. Sensors are planted in plots across a region, acting somewhat like towers in a mobile network. Farmers do not host or manage the hardware, rather they subscribe to the network. InnerPlant’s agronomists send weekly scouting reports during high-risk periods and send alerts by text and email when sensors confirm infection.

“It helps take the guesswork out of fungicide decisions,” said Sean Yokomizo of InnerPlant. “[Farmers] only have to take action when and where it’s needed, rather than spraying entire fields.” Farmers are pragmatic and want clear benefits, he said. Technology has to be low-risk and consistent to win trust.

As of 2025, InnerPlant’s network covers 50,000 acres across the Midwest US, including in Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska and South Dakota. They plan to increase the network to cover more than half a million acres in 2026, and to add insect detection in soybeans in 2027, followed by a corn fungal sensor. The company is also looking into satellite use, with the aim of improving their large‑scale visibility.

Whether or not InnerPlant succeed in their plans, other companies are likely to take advantage of these new technologies. Fluorescent technologies may be particularly helpful in coping with climate change, which is already leading to unpredictable weather patterns. These include raised temperatures and humidity – conditions in which fungal disease can escalate rapidly. An early fluorescent signal lets a grower treat the right block before spores spread further across crops. Blanket “just in case” sprays can become the exception, targeted passes can become the norm, and costs fall – as does the chemical load that runs into streams.

Fluorescence can also help to guide watering practices – which is especially important in times of drought, or where water is expensive or scarce. Plants shift their fluorescent signatures when stressed, often before leaves wilt. If you can see that change early, irrigation moves from routine to need, which saves energy and helps prevent salt build-up in soils. It’s useful for monitoring nutrients, too. If low nitrogen shows up as a clear map rather than a hunch, variable-rate equipment can treat poor zones and skip healthy ones. Yields hold and, again, excess fertiliser stays out of rivers.

Challenges ahead

While fluorescent plants offer a powerful tool for monitoring plant health, they come with significant limitations that justify continued interest in bioluminescent systems. Fluorescence relies on external light sources to excite the fluorescent proteins, meaning it requires specific field conditions, special optics and a clear line of sight to detect the signal accurately. These requirements can make it challenging to implement widespread, real-time monitoring in open agricultural fields.

In contrast, bioluminescent plants produce their own light through biochemical reactions, offering the potential for continuous, autonomous signalling of plant health or stress without external illumination. This intrinsic glow could enable easier, more flexible monitoring in diverse environments and at night, providing a unique approach that fluorescence alone cannot currently offer.

Daniel Voytas, a professor at the University of Minnesota and a leader in plant genome editing, says we shouldn’t give up on bioluminescence as a developing field that could have future applications in agriculture.

Along with engineering plants using the fungal bioluminescent system, researchers are also making good progress with insect systems. “The use of insect luciferases as reporters has been enormously valuable for plant biotechnology research, and I expect their role will continue, if not expand,” Voytas told me. “These are primarily research tools rather than traits in themselves, so their direct impact on agriculture and food security is likely to remain limited compared to other biotechnological approaches,” he acknowledged. But while achieving consistently high levels of luminescence has proven a significant challenge, the science is advancing.

There are many hurdles to overcome, for both bioluminescent and fluorescent technologies. Farms are dirty and unpredictable places. Light signals have to be bright and specific. Models need to be able to tell the difference, for example, between light emitted due to heat stress and light that indicates infection. The challenge is producing a sufficient number of plants that are bright enough to be useful. And even if luminescence improves, the trait still has to deliver under sun and heat, and earn its keep across a season. Some farms can also be reluctant to try new technologies. Mistakes in agriculture can be costly. A false positive, for example signalling disease, could be a huge waste of time and money.

Regulators will continue to ask hard questions, too. There’s no sign yet that the trait that causes plants to glow can spread by pollen, but these questions about gene flow are sensitive, and must be carefully tested and monitored. If the ability to glow draws on more of a plant’s metabolism (in other words, the energy available to them) then it may slow their growth, or ability to produce seeds or fruit.

Public acceptance is important too, given many people have negative attitudes towards genetically engineered crops. Light Bio believes that their ornamental plants can play an important role in shifting public perception. “Crop development through genetic manipulation is vital to global food security,” Wood said. “By giving the public a tangible, positive experience with a glowing plant, we believe we can help build familiarity and trust.”

When I asked him about the future, he said he expects brighter and more varied glowing plants to be developed over the next decade. “We’re improving the genetics, and we’re improving the methods of production,” he said. “I expect we’ll get brighter plants, more robust plants.”

A farming revolution?

Meanwhile, bioluminescence and fluorescence will continue to allow scientists to study plant physiology, with discoveries feeding back into knowledge around how to develop better and stronger bioluminescent traits, creating a positive cycle of learning and development.

Yokomizo of InnerPlant believes that advances in the study of the genetic processes of plants, combined with the use of bioluminescent and fluorescent traits in crops out on the field, represents a revolutionary opportunity in farming. “Data from plants has always been the missing component all the way back to the beginning of agriculture,” he said. “Finally having that critical data will change farming practices in a very fundamental way, just as the Green Revolution did.”

He’s referring to rapid changes that took place in farming in the mid-20th century, including the development of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser. There was also progress in breeding plants in order to create hybrid seeds, known as high-yielding varieties, which are more responsive to fertilisers, and better at adapting and resisting disease. All of this triggered major economic growth in agricultural regions worldwide.

It’s a bold comparison, and it should be treated as speculative. We don’t yet know whether bioluminescence and fluorescence will have revolutionary effects on the future of agriculture. It is more cautious to say that clear, early signals can help reduce waste and protect yields.

For now, bioluminescence and fluorescence will remain a powerful research tool, and field deployment should expand as engineering advances. In the meantime, ornamental plants serve a quieter purpose. They show biotechnology as something beautiful, not only as a risk. It’s a shift in perception that can help us imagine what could come next…

In late summer, a soybean grower gets a text: four fields crossed a fungal threshold overnight. The sprayer rolls that day, but only across those blocks. Time, money and effort are saved, and environmental impacts are reduced.

At a nearby farm, nitrogen goes only where the signal shows deficiency. The field map turns patchy and precise, which is how real land behaves.

At the packhouse, a bioluminescent signal flags contamination before a pallet of bananas is loaded onto a ship. The win is invisible but crucial, as prevention usually is.

Most of the time, we won’t see the light with the naked eye. But some day in the future, it may be a common occurrence to drive past a farmer’s field at night and notice a faint but magical glow.

This article is from New Humanist's Winter 2025 edition. Subscribe now.

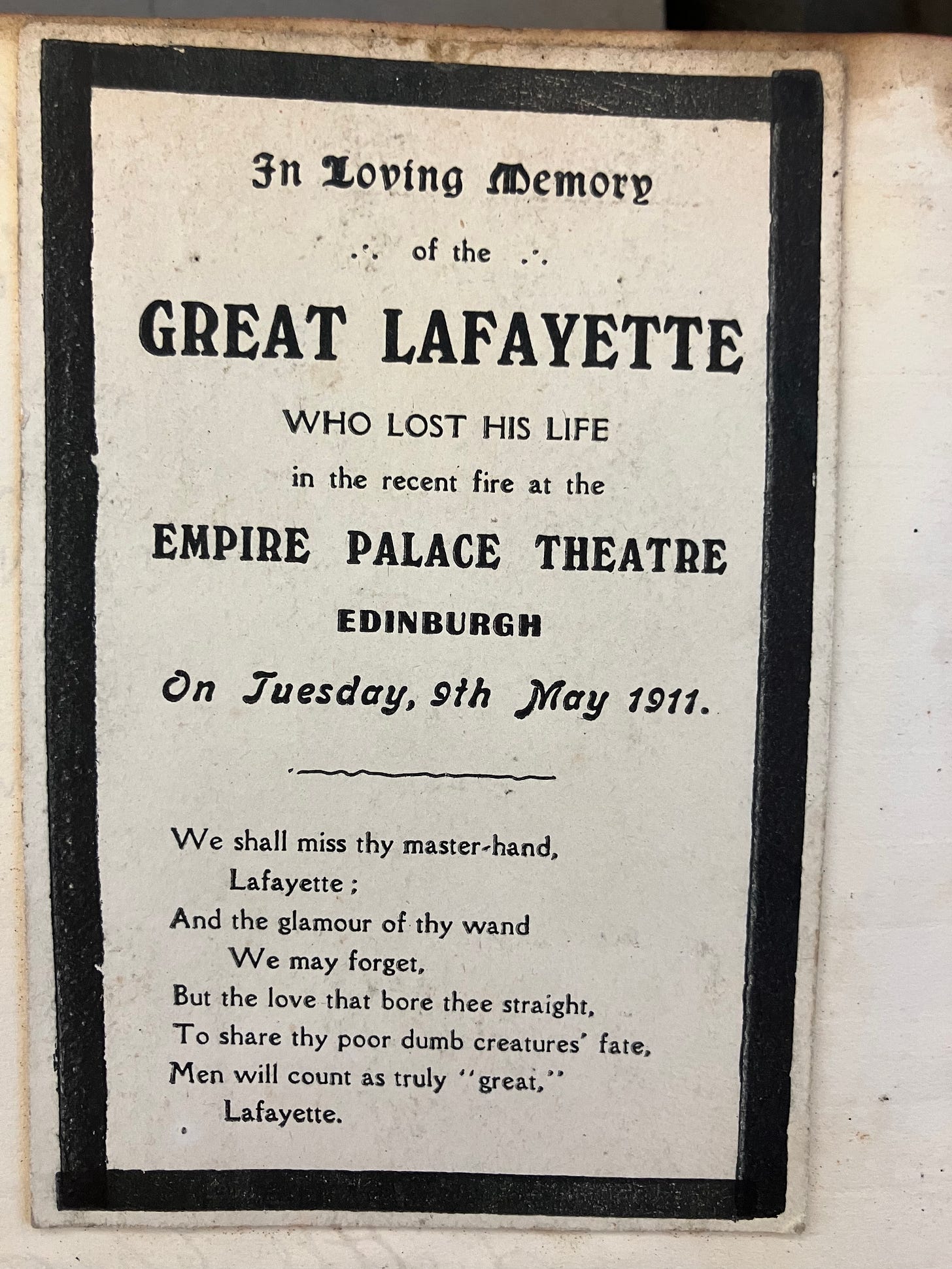

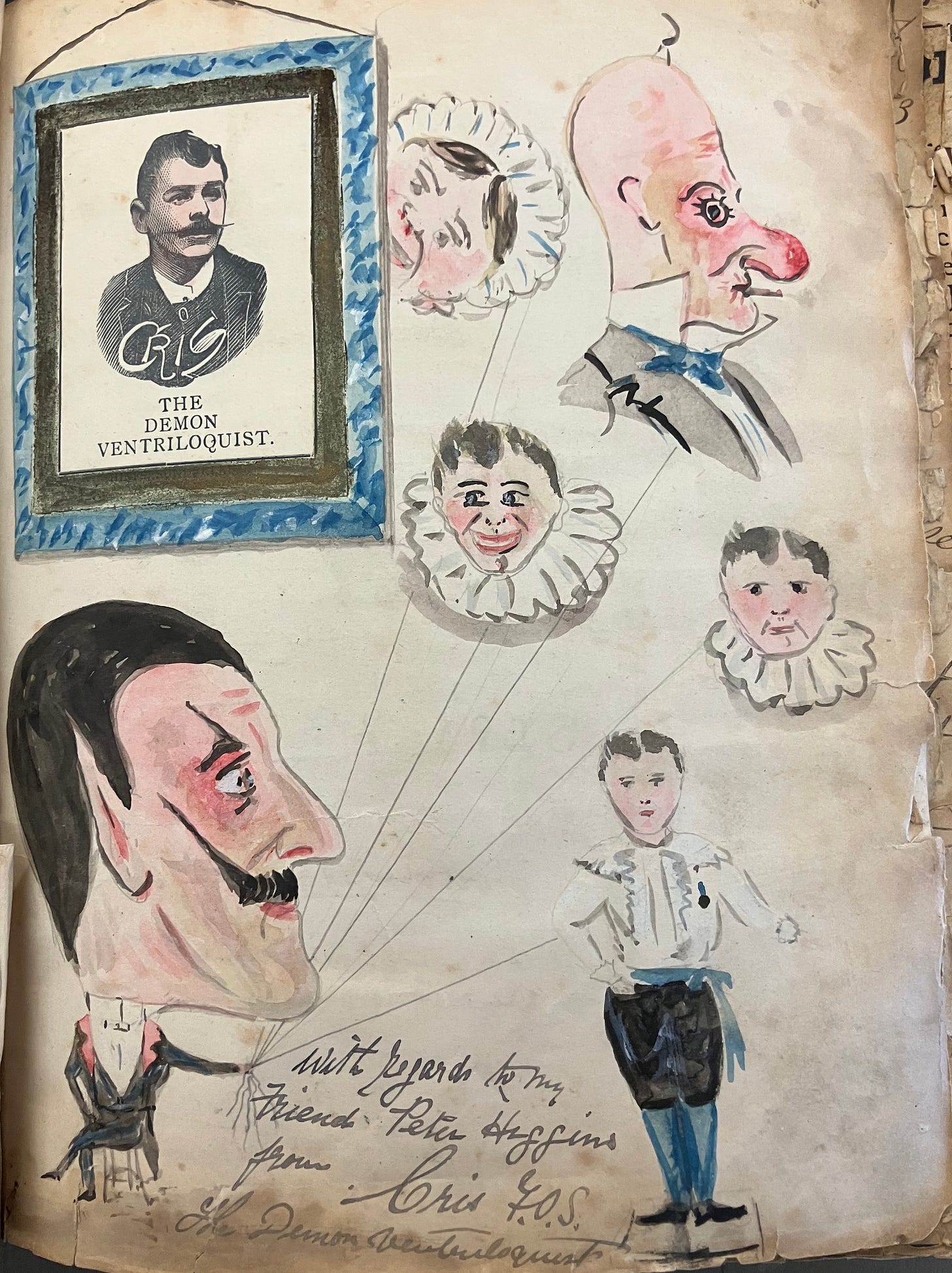

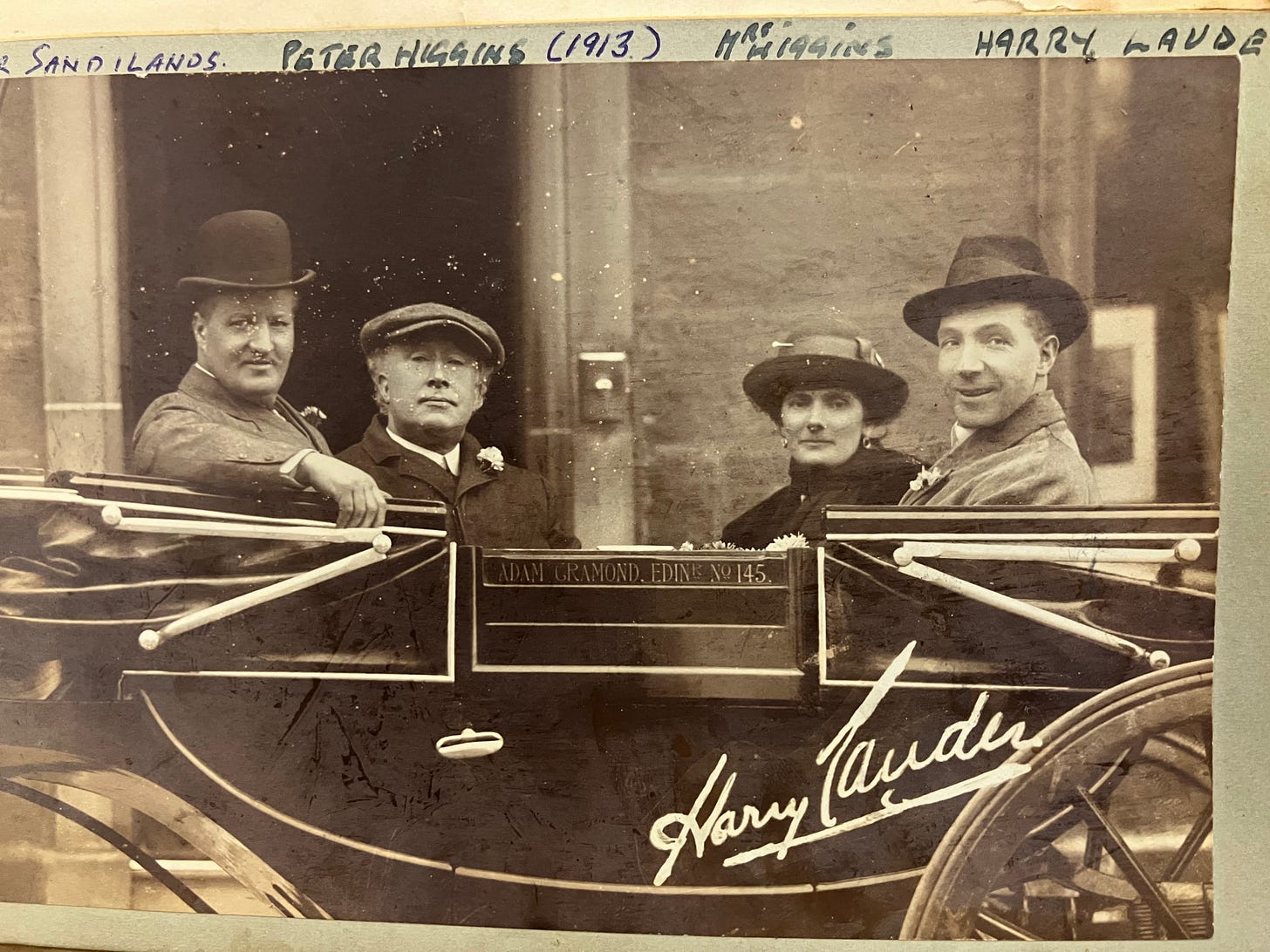

It’s time for some obscure magic and music hall history.

I’m a fan of a remarkable Scottish conjurer called Harry Marvello. He was performing during the early 1900s and built a theatre in Edinburgh that is now an amusement arcade. I have a previous post on Marvello here and have just written a long article about him for a magic history magazine called Gibecière (the issue is out soon).

I am staging a one-off performance of the World’s Most Boring Card Trick at Magic Fest in Edinburgh on the 27th December. Tickets here. Anyway, I digress. I have long been fascinated by the psychology of humour and once carried out a project called LaughLab. Billed as the search for the world’s funniest joke, over 350,000 people submitted their top gags to our website and rated the jokes sent in by others. We ended up with around 40,000 jokes and you can read the winning entry here (there is also a free download of 1000 jokes from the project).

It was a great project and is still quoted by media around the world. I ended up dressing as a giant chicken, interviewing a clown on Freud’s couch, and brain scanning someone listening to jokes.

A few years ago, I came up with a theory about Christmas cracker jokes. They tend to be short and not very funny, and it occurred to me that this is a brilliant idea. Why? Because if the joke’s good but you don’t get a laugh, then it’s your problem. However, if the joke’s bad and you don’t get a laugh, then you can blame your material! So, cracker jokes don’t embarrass anyone. Not only that, but the resulting groan binds people together. I love it when the psychology of everyday life turns out to be more complex and interesting than it first appears! As comedian and musician Victor Borge once said, humour is often the shortest distance between people.

I recently went through the LaughLab database and pulled out some cracker jokes to make your groan and bond:

– What kind of murderer has fibre? A cereal killer.

– What do you call a fly with no wings? A walk.

– What lies on the bottom of the ocean and shakes? A nervous wreck.

– Two cows are in a field. One cow: “moo”. Other cow: “I was going to say that”

– What did the landlord say as he threw Shakespeare out of his pub? “You’re Bard!”

– Two aerials got married. The ceremony was rubbish but the reception was brilliant.

– What do you call a boomerang that doesn’t come back? A stick.

– A skeleton walks into a pub and orders a pint of beer and a mop.

The BBC have just produced an article about it all and were kind enough to interview me about my theory here.

Does the theory resonate with you? What’s your favourite cracker joke?

Have a good break!

First, a quick announcement – I will be presenting a special, one-off, performance of The World’s Most Boring Card Trick at the Edinburgh MagiFest this year. At a time when everyone is trying to get your attention, this unusual show is designed to be dull. Have you got what it takes to sit through the most tedious show ever and receive a certificate verifying your extraordinary willpower? You can leave anytime, and success is an empty auditorium. I rarely perform this show, and so an excited and delighted to be presenting it at the festival. Details here.

Now for the story. When I was a kid, I was fascinated by a magazine called World of Wonder (WoW). Each week it contained a great mix of history, science, geography and much more, and all the stories were illustrated with wonderful images. I was especially delighted when WoW ran a multi-part series on magicians, featuring some of the biggest names in the business. My favourite story by far was based around the great Danish-American illusionist Dante, and the huge, colourful, double page spread became etched into my mind.

A few years ago, I wrote to the owners of WoW, asking if they had the original artwork from the Dante article. They kindly replied, explaining that the piece had been lost in the mists of time. And that was that.

Then, in July I attended the huge magic convention in Italy called FISM. I was walking past one of the stalls that had magic stuff for sale, and noticed an old Dutch edition of WoW containing the Dante spread. I explained how the piece played a key role in my childhood, and was astonished when the seller reached under his table and pulled out the original artwork! Apparently, he had picked it up in a Parisian flea market many, many, years ago! The chances!

I snapped it up and it now has pride of place on my wall (special thanks to illusion builder Thomas Moore for helping to make it all happen!). My pal Chris Power made some enquirers and thinks that the art was drawn by Eustaquio Segrelles, but any additional information about the illustration is more than welcome.

So there you go – some real magic from a magic convention!

Subscribe

Subscribe OPML

OPML